How many bushels of wheat do you make a year? While this is not the most relevant question to be asking about wages today, some of the discussion around the minimum wage is taking inspiration from a very old economic idea according to which questions like this would be right at home. The idea is that of a “wage fund”: a fixed amount of total wages available to an economy for a given period that dictates the average wage. If such a fund exists, then any aim to raise wages within the period for which the fund is fixed will inevitably end up harming workers – most likely those with the lowest wages and the least power. Today’s arguments against increasing the minimum wage at times mirror this flawed logic – and for reasons that, oddly enough, reflect on why the theory was discarded in the first place. (Click here if you want to skip the history and get to the present; otherwise read on.)

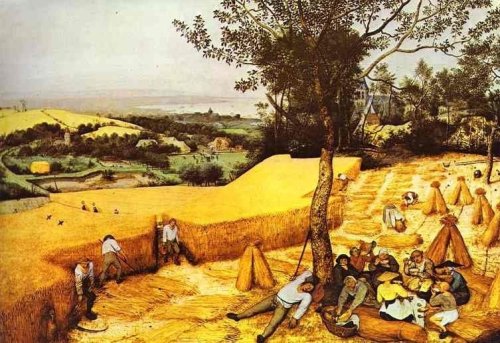

The origins of the idea of a wage fund date back to the largely-agrarian economies of the 17th and 18th centuries within which early classical economics developed. Adam Smith included the wage fund as a short-run determinant of wages in The Wealth of Nations; he got the idea from the Physiocrats, an earlier schools of French economists. The theory survived for over a century after Smith and its most famous exponent, the late 19th-century philosopher and economist J.S. Mill, ended up being amongst its last.

The wage fund is stylized to reflect an economy where the bulk of wages go towards procuring the products of agriculture as food. In a simple agricultural economy, there is a lag between sowing and reaping, which means that the size of harvest to be available as food is fixed long before it is gathered and sold. Each production period (say, a year) therefore has a fixed fund of agricultural produce that will appear at the end of the period. This fund is then slowly advanced to workers over the course of the next production period; as such its magnitude is fixed and can only change when the following production period begins and even then generally not by much as agricultural technology and the amount of agricultural land were thought to be relatively stable. The total sum of wages was thus largely fixed in the short- and medium-term; only in the long term could population growth and technology impact on its rise and fall.

The wage fund theory was used in the 19th century to argue against worker agitation for higher wages. Union formation, strikes and other tactics that aimed at increasing wages were derided as fool-hardy. If these tactics were targeted at the general wage level of all workers, they could only lead to higher prices that left real wages unchanged; if they were aimed at the wages of specific groups, any real wage increases won by some would be cancelled out by falling wages for others.

The wage fund relies on a decidedly static view of the economy, at least in the short run. As a theory of distribution, it follows the classical tradition in primarily taking collectives rather than individuals as its object. It is a theory of classes – those who draw on the wage fund and those who own and administer its contents, that is, workers and capitalists. The dynamic of power between these groups is already resolved, however: workers can gain no more and no less than the contents of the wage fund and the fund is proportional to their (culturally-determined) subsistence.

Neoclassical economics discarded the wage fund theory in its entirety: its primary flaw was seen to be precisely the static treatment of large economic aggregates like wages and reliance on collectives. Rather than a stock to be divided by a class, wages were reconceived as a flow that corresponds to the productivity of the individual worker at the margin of production. The wage is equal to the increase in the value of production that would result in hiring one more worker. The wage fund left no room for the movements and adjustments in the economy: changing technology, different savings patterns, shifting tastes – all factors that potentially affect the relative contributions of capital and labour and could lead to the substitution of capital for labour or vice versa in production. The new theory – one that persists as the mainstream account until today, albeit with qualifications for market imperfections made by some – is dynamic and individualist.

So what of the wage fund today? No contemporary commentator will openly ascribe their opinion to this antiquated, agrarian-derived theory. Its echoes, however, ring out loudly from between the lines of opponents to raising the minimum wage in the debate raging across Canada and the US – especially as there have been some limited successes on both sides of the border. Here is a typical snippet:

The reality is that increasing the minimum wage will help some workers, who will be paid more, at the expense of many other workers who will either lose their jobs or never be hired in the first place. (National Post)

And another from a few weeks ago in a very similar vein:

When governments impose a wage floor higher than what would prevail in a competitive market, employers find ways to operate with fewer workers. While the more productive workers who keep their jobs gain through higher wages, their gain comes at the expense of other workers who lose as a result of fewer employment opportunities. Young and low skilled workers usually end up as collateral damage in the process. (Financial Post)

The argument is a little different but the flavour is the same as the wage fund. The classical wage fund theory was conceived on the assumption of full employment in an economy without any of the protections of the welfare state. This led its proponents to believe that employment would stay fixed if workers agitated for higher wages but that wages would fall via price increases or a different distribution of the fund. Today, the argument remains that the pie going to workers is only so big, any way you slice it. The difference is that most argue that giving some workers a slightly larger slice in the form of a mandated minimum wage is tantamount to taking a piece away from other workers entirely. Either way, there is only so much in wages to go around.

Call this a static-like individualism. The individualist, productivity-based explanations of modern economics are combined with a view that ultimately there is something akin to a fixed amount to go around for workers, especially those at the bottom. (A more “advanced” version of this thesis – variously called New Classical economics or Real Business Cycles theory – actually adopts the classical assumption that the economy is always at full employment and no meaningful disequilibrium such as persistent unemployment is possible. In its crudest form, it claims that the price mechanism will work itself out almost instantly so that workers are ultimately left no better off via higher minimum wages.)

For today’s opponents of the minimum wage who end up channeling the wage fund view, the worse outcomes for workers are no longer about the fact that workers as a collective have too little power; the problem is instead an individual one of insufficient productivity. Low wages are just desserts for personal inadequacy in helping society produce wealth. While the classical wage fund doctrine focuses on losses to workers in general and takes subsistence as its baseline for most workers, the contemporary position puts a finer point on it: raising minimum wages hurts that very small portion of the lowest-paid workers that the policy is trying to help. These workers are the weakest and are such because they have the least to contribute. In some ways, this is a more refined and pernicious version of the doctrine.

Much solid empirical economic research counters this view. Evidence shows that raising the minimum wage has no significant effects of lowering employment (and may even increase it) and also has the potential to reduce poverty and improve other outcomes. The mechanisms vary but include lower turnover, greater productivity from training or simple motivation for work and economy-wide multiplier effects of increased demand. These results stem from a more dynamic perspective that shows minimum wage policies to have broader impacts far beyond simple redistribution between workers. They remain, however, at the level of the individual.

To concentrate solely on individual-based responses to minimum wage policy does not pay enough attention to how wage gains and other improvements are cemented, while at the same time giving too much credit to those who would blame low wages on the workers who receive them or unemployment on those in line at the benefits office. As the classical expounders of the wage fund doctrine were aware, wage battles are a collective matter and the wage fund doctrine treated them as such. Today’s conservative commentators have been able to marry a version of this doctrine with calls for greater worker flexibility to pit working people against one another.

To counter this harmful tendency to see social problems as individual ones, the collective aspect of labour policy needs to be placed at centre. Of course, one of the most interesting polemics against the wage fund belongs to Karl Marx, who delivered it in series of speeches that were later published as a pamphlet under the title Value, Price and Profit. In typically colourful language, Marx writes,

[My opponent]…has forgotten that the bowl from which the workmen eat is filled with the whole produce of national labour, and that what prevents them fetching more out of it is neither the narrowness of the bowl nor the scantiness of its contents, but only the smallness of their spoons.

Today, while we have solid arguments that talk about the size of the bowl, the real work is in ensuring that people are able to together fashion those bigger spoons. Recognition for this fact is comes from all manner of places. For example, even a recent IMF report concluded that if we’re to be serious about combating rising inequality then “restoration of poor and middle income households’ bargaining power can be very effective.” The New York Times also published a recent editorial stating that the “real argument against [raising the minimum wage] is political, not economic,” recognizing the collective element.

The minimum wage is but one small tool that works to slowly shift the balance of bargaining power; I’ve written before that we need stronger and bigger unions, public services and more. Marx would have called it class power and his analysis is slowly making a comeback in some regards and in unfamiliar places. Either way, in the case of low-wage work, collective strategies are all the more necessary because of the gendered and racialized nature of this work that only increases individual difficulties. Campaigns like those led by fast food workers and others calling for a $15 minimum wage across the USA and the $14 Now! campaign in Ontario show how to workers can organize together, perhaps in non-traditional ways, and move the debate forward.

Some will continue to argue that there are effectively only so many wheat kernels to go around and that workers are destined to fight over them amongst one another. Paying attention to the broader dynamics of the economy and collective solutions that build power, workers can show these arguments to be worth nothing more than a loaf of Wonderbread.

3 replies on “Economic history in the present: The wage fund and the minimum wage”

Reblogged this on The Left Eye.

[…] Read more. […]

[…] Does a minimum wage increase hurt workers? The problem is only the smallness of their spoons: http://politicalehconomy.wordpress.com/2014/02/10/economic-history-in-the-present-the-wage-fund-and-… […]