Yesterday’s federal budget was a non-event. Indeed, the no-surprises budget was itself no surprise: the Conservatives have long done their fiscal policy dirty work in omnibus bills and other dark corners scattered throughout the legislature, Crown corporations and federal agencies. This leaves the media circus of budget day a very stereotypically Canadian mix of polite and boring. Canada’s is a slow-motion austerity and the current budget is a continuation.

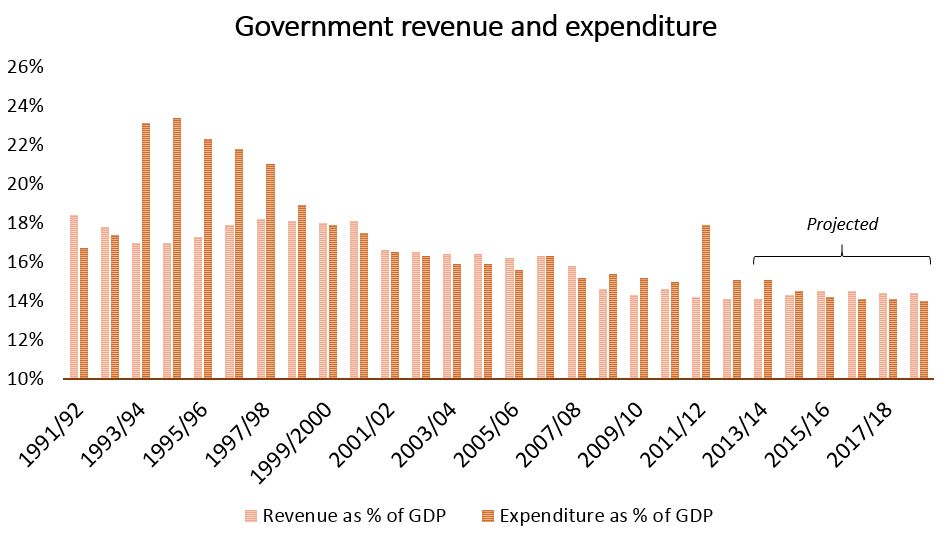

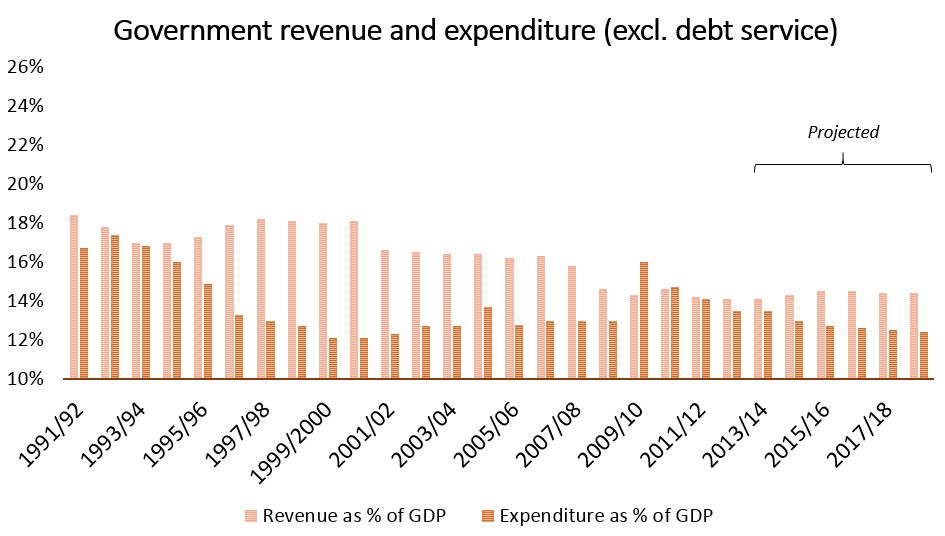

To be sure, there were big-ticket announcements: a few bridges for cities, some internet for rural areas, internships for the young, factories for auto makers… The government, after all, still does something. This doing, however, is undergoing a slow-but-steady transformation. Federal government expenditures relative to GDP have been in secular decline for three decades and revenues relative to GDP have been shrinking steadily for over ten years as well. Projections contained in the current budget have both of these trends continuing, especially in terms of expenditures – and especially if only program expenditures without debt service costs are taken into account.

A large portion of the already small bag of newly-announced expenditures reflects the difference between “new” and “announced” more than anything else. Indeed, fully half of the spending measures have been previously announced and ear-marked, including the Jobs Grant program and portions of big-ticket infrastructure spending on projects such as the planned bridge over the Saint Laurence in Montreal. Some measures are simply a slap in the face: the budget proudly proclaims that 200 new food inspectors will be hired, while leaving out the fact that 1400 such positions were just cut – a net loss of 1200 jobs.

The current brand of austerity has had no dramatic or drastic cuts, only a slow withering of government, matched by an expansion of the private sector into previously public spheres of economic life, a greater concentration of wealth and a laxer regulatory regime. Expenditures are allowed to fall away and cuts are often hidden or enlarged in other legislation. On the other side of the ledger, new spending is rarely significant, often simply finely-targeted to score political points.

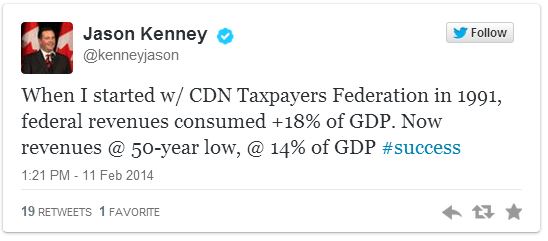

Indeed, some of the most important economic work done by the Conservatives is a day-to-day ideological battle about framing the terms of the economic debate. Here, they have achieved success: survey results released just before the budget show that most Canadians – and even the majority of supporters of each of the three major political parties – support balancing the budget before increasing spending. Jason Kenney tweeted the extent of this success after the budget was tabled:

The bravado is, sadly, well-deserved. This snippet reveals not only the strongly ideological affinities between the Conservative government and business lobby groups like the Taxpayer’s Federation; it shows how the public sector is painted as a sinkhole for money – government merely “consumes” GDP and cannot contribute to a thriving economy. This picture of government is used to support the need for fiscal “responsibility” in the form of budget balance and bolster slow transformation towards increased private provision of once-public goods and services.

Those in power who subscribe to this view can therefore easily square a firm commitment to a radically smaller public sector achieved through cuts to taxes and expenditures with the use of temporarily-higher government spending. For adherents, government spending is relatively ineffective on its own in normal times, but it can be used as a tool to generate election wins that will enable further cuts – this is its instrumental value. The “stimulus budgets” of 2009 and 2010 can be partly seen in this light; however, they were in larger part about bailing out the private sector from its own mistakes. The budget of 2015 will likely be a much better example of politically instrumental use of spending aimed at electoral gains more than fiscal solutions to the structural problems of the economy that affect the bulk of Canadians – a weak job market and inflated debt loads amongst the most pressing.

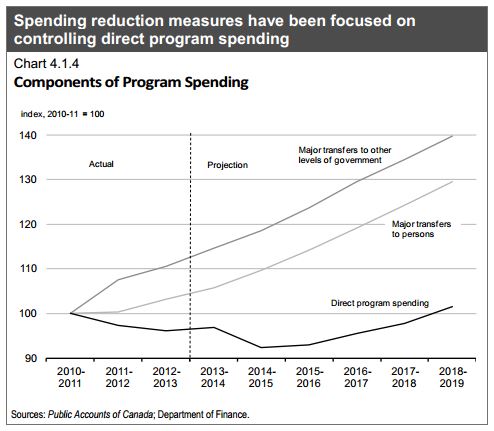

The changes brought about by the Conservatives appear particularly well in the different projected trajectories of program spending and individual transfers.

The government is effectively freezing direct program spending over the next five fiscal years – in other words, there will be a real reduction in such spending once inflation is taken into account. Only transfers are intended to keep pace with projected inflation and economic growth. Austerity today means that not only are government expenditures falling relative to the size of the economy, direct expenditures are making for nearly the entirety of this drop. The role in transforming the economy is clear: transfers such as tax credits and direct payments are not equivalent to social programs precisely because they can contribute to limiting public provision.

In addition, much of the reduction in program spending is coming on the backs of public sector workers. One of the changes introduced in the 2014 budget will see retirees from the public service contribute twice as much to health care plan: their share of plan costs will rise from 25% to 50%. The budget forecasts that overall total compensation spending on current and retired public sector employees will fall by $1.5 billion in just the upcoming fiscal year.

In the labour market, austerity means not only cuts but transformation. This government policy of a spending freeze is helping undermine working Canadians who face a crisis of good jobs. Public sector cuts undermine unions as effectively as changes to labour legislation or cuts at Crown corporations at Canada Post, where 8000 workers are set to lose their jobs due to ill-planned cost-cutting. These cuts send the same message as the budget’s announcement of 4000 internships to deal with youth unemployment (a paltry measure for the almost 400,000 young Canadians without a job): good jobs are gone. Welcome to the world of the precariously-employed – the self-employed, the involuntary part-timers, the interns – less able to fight for their fair share of economic gains. These changes to the labour market give an idea of how austerity goes far beyond simple reductions in the size of government.

The overarching story in which the just-released budget is but a boring blip is one of a slow transformation of both the government sector and the broader economy. Canada’s 2014 budget is really just another case of another day…another dollar cut, another job made precarious, another market opened. The missing dollars, the precarious jobs and the privatized services add up, however. Dozing even on this slow-moving train, we will one day wake up somewhere radically different.

3 replies on “Another (budget) day, another dollar (cut): Canada’s slow-motion austerity”

[…] Political Eh-conomy – Another (budget) day, another dollar (cut): Canada’s slow-motion aust… […]

[…] as many, including myself, have argued, we currently face a growing crisis in government revenue. As a percentage of GDP, […]

[…] is best described as a creeping, slow-motion austerity. Stephen Gordon actually nicely diagnosed what this has looked like most recently (since about […]