Alright, so the title is a bit of a cheap hook, taking advantage of the popularity of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. In his book, French economist Piketty traces the contours of global inequalities of wealth (and income) over the past 300 years and wraps them in a novel and thought-provoking theory of economic dynamics. Inspired by this general theme, I present here a smattering of numbers and thoughts on the links between inequality in Canada and the concentration of hydrocarbon (oil and natural gas) resources.

Piketty mentions Canada several times and only fairly incidentally. On initially flipping through the book, however, I came upon a short section tucked away in one of the last chapters. The section is titled “The Redistribution of Petroleum Rents” and it has some very direct relevance for Canada. In it, Piketty writes,

When it comes to regulating global capitalism and the inequalities it generates, the geographic distribution of natural resources and especially of “petroleum rents” constitutes a special problem.

The remaining page and a half of this very short section is taken up with Piketty’s musings on the two most recent Iraq wars, on the injustices that can develop in petro-states and on how conflict over unequally-distributed of oil can differ from democratic ideals.

The general “special problem” of petroleum rents, however, also applies to Canada. Canada is an interesting case because oil (among other resources) is geographically very unequally distributed within its national borders. Overlaying the unequal geographic distribution is a federation in which provincial governments operate within the same very broad institutional bounds but can yet differ substantially on policy in a wide range of areas. Indeed, Canadian provinces are sometimes compared, in their powers, more to very delimited states than sub-national jurisdictions.

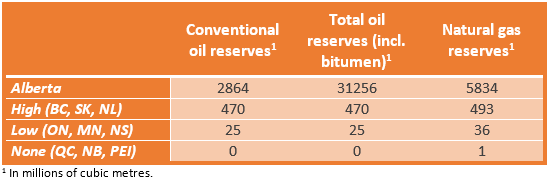

The table above gives a good idea of the unequal distribution of hydrocarbons within Canada; these are total original reserves, of which only a portion still exists. I’ve divided provinces into four categories. Alberta is, of course, the clear outlier. The provinces in the middle two categories have some differences, with some having more oil and some more natural gas, but are overall easily sorted into those categories.

An inequality of natural wealth that can generate inequalities in streams of income – in other words, petroleum rents. Rents from petroleum are not quite the same as those from the traditional sources of rent, like land, but they are close. While land has a fixed and stable supply, petroleum and other hydrocarbons are used up when exploited. Petroleum rents reflect this fact and its attendant that hydrocarbons require effort and resources to unearth. These rents are commonly presented as the difference between the cost of production and the price on world markets.

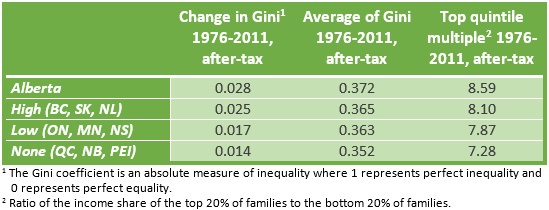

Table 2 shows some of the differences in income inequality when provinces are grouped according to the extent of their hydrocarbon reserves. The trends are quite clear (the dates were chosen based on the availability of data). All of the measures of inequality correlate well with the extent of hydrocarbon reserves. In addition, the vast majority of the differences are statistically significant (for those interested, most of the p-values are below 0.01; only the difference between the High and Low groups turned out to be insignificant at the 10% level – both on the Gini and quintile measures).

In taking the province as the unit of analysis, their relative size in terms of population does not matter. The point is to compare institutional structures across jurisdictions depending on whether these were lucky or unlucky enough to sit over top of reserves of hydrocarbons.

This is also the reason for focusing on after-tax incomes. After-tax incomes reflect the effect that petroleum rents can have on institutional structures. Take systems of taxation as an example, where Alberta’s flat tax on income is an egregious outlier – it is the outcome of a long-building fiscal conservatism made politically feasible in no small part by petroleum. If some argue that Canada is on its way to becoming a petro-state in its institutions, then Alberta surely is the petro-beachhead. The data seems to bear this out as differences in inequalities in this, final, form of income are more pronounced when grouped by hydrocarbon reserves than those in market incomes.

These differences in inequality of citizen incomes within provinces dovetail with inequalities between provincial governments. The CCPA has recently published work on the disparities in fiscal capacities of provinces and shown that these are related to the influx of petroleum revenues, particularly when it comes to Alberta.

So, in short, provinces with greater hydrocarbon reserves exhibit greater internal inequality of incomes. In the spirit of Piketty, I hope that this correlation is but the launching point for more interesting investigations, but in the spirit of Doug Henwood’s review of Piketty, I hope these lead to radical political engagement.

I and many others have been critical of the current fascination with “data-driven journalism” that often ends up throwing some charts and graphs at readers, either taking the correlations these show as theories in themselves or wrapping them in quickly-assembled, often shoddy theory.

So, for now, there is no claim to a theory here…yet. So far these are just some assembled observations that strongly suggest a theory — one that will almost certainly involve plutocracy, cooptation and institutional decay. For now, however, a bucket of cold analytical water to bring out a genuine curiosity. One that will hopefully sharpen the patterns in inequality within Canada based on the distribution of hydrocarbon resources.

The existence of petroleum rents is not only a source of inequality in initial resources, but the exploitation of these resources appears to also have far-reaching ramifications for the different evolution of institutions, even within a Northern country like Canada.

The correlations here might turn out to be of the piracy-climate change variety, but there are good reasons to think they point to something genuinely interesting. What’s needed is more patterns, more time and more thought. And a good theory that would stretch the possibilities of this single blog post too far. In even shorter, lots of work to be done.

6 replies on “Piketty on Canada: Oil and inequality”

Very interesting work Michal! I think the numbers are definitely suggestive of a connection, especially given that you used the change in Gini rather than its level. This is also an interesting case of the correlation/causation distinction because it’s hard to imagine fossil fuel reserve size being jointly caused by something that’s also driving inequality, since fossil fuel reserves were determined long before humans were around to start causing things (although, the extent of exploration and discovery of reserves certainly plays a role in the estimated reserve sizes). I think it would be nice to also look at annual extraction rather than reserves to see how that relationship compares.

Thanks Len! Yes, I think that the impossibility of arguing causality in the other direction adds to the case that there is something to these trends. I used the amount of reserves because I think extraction rates are (1) harder to find a precise time series for, (2) could be too volatile and (3) could reflect on a bunch of co-variates whereas large reserves are more indicative of a fundamental resource bias to an economy that creates deeper inequality-producing trends. Which isn’t to say that it wouldn’t be very useful and interesting to look at the extraction-inequality relationship and what it shows.

The US may afford the best comparison given the similar divisions of power between state and federal government and the unequal distribution of oil wealth (Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, California). Norway would be useful to examine given its similarity in climate and development but vastly different approach to its oil wealth than Alberta. Russia would also be an interesting country to look at given its massive territory and similarly unequal distribution of resources.

Andrew Nikiforuk devoted a section of his book, Tar Sands, on the political ramifications of oil wealth suggesting that oil wealth hinders democracy and increases corruption. The single party rule in Alberta (43 years) would certainly fit in comparison to other provinces. Nikiforuk cites studies by Micheal Ross showing a negative correlation between democracy scores and oil wealth among 113 nations over a 26 year period. Ross suggests various mechanisms by which this occurs which all seem to be a result of increased fiscal capacity: absence of taxation, extra money for propaganda and squashing of dissent, and money for militarization. Nikiforuk also cites a study by Erik Wibbels and Ellis Goldberg that looked at elections in U.S states over a 73 year period and found that oil, coal, and gas wealth had a significant effect on the outcome of elections in favour of incumbents.

There has also been a lot of work on the relationships between democracy and inequality, democracy and development, as well as oil wealth and development which may provide additional insight into the mechanisms behind the relationship you’ve presented above.

Here are the citations for those studies:

Ross, Michael. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics 53 (April 2001).

————. “Does Resource Wealth Cause Authoritarian Rule?” Presentation at Yale

University, 10 April 2000.

Goldberg, Ellis, Erik Wibbels, and Eric Mvukiyehe. “Lessons from Strange Cases:

Democracy, Development and the Resource Curse in the U.S. States.” Comparative

Political Studies 41:4–5 (2008)

Wibbels, Erik, and Ellis Goldberg. Natural Resources, Development and Democracy: The

Quest for Mechanisms, 2007. Available at http://sitemaker.umich.edu/comparative.

speaker.series/files/wibbels_9_07.pdf and http://media.hoover.org/documents/

Wibbels_Stanford_paper2.pdf

Tar Sands is available in print or ebook here: http://www.greystonebooks.com/book_details.php?isbn_upc=9781553655558

Thanks for all this! I’ll have to give it a look through before coming up with a more substantive response but at least some of it seems like the kind of work I was thinking of to provide more context to the numbers in this post.

While we’re on the topic, Andrew Nikiforuk has an interesting article in the Tyee today on the crisis in Ukraine and its relationship to oil and gas:

http://thetyee.ca/Opinion/2014/03/27/Ukraine-Crisis-Global-Energy/