Jonathan Kay knows what’s hurting the poor. Is it absurdly low welfare rates and social supports? Perhaps it is lack of access to affordable housing? Poverty wages? Food insecurity? Over-policing? No, says Kay, the honest broker of politics, the inconvenient truth-speaker, it’s the left’s political correctness that’s really keeping the poor down.

Kay supports this claim with a jumble of obvious facts, unexamined assumptions and misrepresentations held together like the remnants of the fraying neoliberal consensus. In his most recent Walrus editorial, Kay jumps from (1) houses in Vancouver cost too much (true) to (2) it’s all the fault of the Chinese (nope) to (3) the left doesn’t care about class or the poor (wtf), all in the span of under 900 words! Here’s the punchline, complete with the obligatory reference to “things I’ve seen on social media”:

The left now has a golden opportunity to push for bold policies that would go to the heart of income inequality in our class-based society: guaranteed income, universal access to care for those suffering from mental illness, and, yes, tax and regulatory policies that discourage hot money from overinflating local real-estate markets. But from what I’ve read on social media and in Walrus editorial submissions, many activists and pundits seem far more comfortable striking positions on highly compartmentalized identity-politics issues that can be reduced to succinct, tweet-able messages.

For someone who has so much sage advice for the left on class politics, Kay is utterly oblivious to how class operates. Kay castigates Vancouver mayor Gregor Robertson for not speaking out against the real estate bubble ballooning under his watch and blames it on steadfast anti-racism. Is Robertson a bleeding heart liberal hopelessly in the clutches of radical dogmas or is it rather that he is the leader of a party that received hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from real estate developers in the city?

There’s no point in citing the innumerable left articles, speeches, rallies, occupations, forums, talks and leaflets on the topics of “socio-economic stratification, poverty, and income inequality” that Kay claims are missing. What better proof that the left has managed to get all of these issues onto the agenda than the fact that clueless elite scribes like Kay are forced to treat them seriously?

Then again, here’s just one example, from this very blog back in 2014 on the same topic of Vancouver’s unaffordable housing:

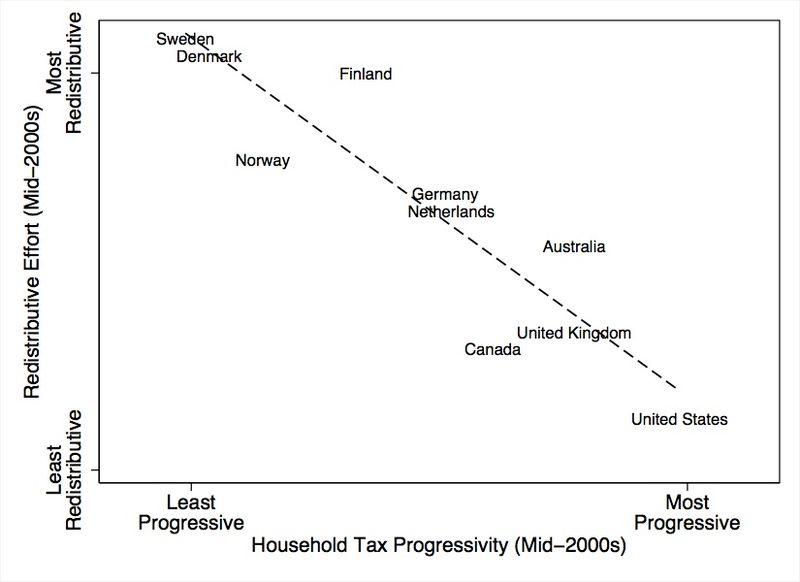

The growth of inequality, attacks on pensions, increases in lifespans, aggressive tax cuts – all of these factors have moved wealthier Canadian households to look for new investment opportunities. Investment in real estate has been helped by low mortgage rates, a supply of new housing skewed towards small, high-end condominiums as well as existing equity available to those who lucked out and grew rich on the initial housing boom that started in Vancouver in the 1980s.

As absurd as it is to say it explicitly, it’s not a hegemonic anti-racism that’s driving millennials and the poor out of cities like Vancouver. It is the combination of record low interest rates and money pumping pushing up asset prices all over the world. Art auctions are breaking records and condos are selling like hot cakes because the rich have won—they no longer have to make productive investments that will boost the wages of regular folks alongside boosting their wealth. It is also government at all levels completely abandoning the project of house-building. The Liberals in the 1990s announced that the Canadian government was “not in the business of housing” and turned to driving private mortgage finance instead.

It is a global glut of too much money chasing too little tangible wealth. Just by virtue of proximity, money from mainland China plays some role in the housing bubbles in Hong Kong, Sydney or Vancouver. But is money from mainland China pricing people out of New York City? out of London? out of Amsterdam? Everywhere it is the wealthy who are pushing out the poor. Developer-funded crocodile tears, not anti-racism, are stopping meaningful reform that would include progressively taxing wealth, wherever its owners are domiciled.

Kay mentions that the average individual income in Vancouver is $43,000. The average for recent immigrants is about half that. The overall median is closer to $30,000. Here’s an opportunity for class and anti-racist politics; the kind already pushing for a higher minimum wage and pushing back against developers. It’s one where the poor, the working class and the racialized have autonomy over solutions rather than being told inequality is a big problem elites should solve. Maybe Kay’s protests and lamentations about Uberization or union weakness would be more believable if they didn’t come from an avid fan of Uber who “won’t go back to cabs” (and whose big solution is to cash out cabbies with a one-time payment) or someone who has wasted hundreds of column inches attacking unions of all stripes.

The truly blind to the class politics screwing workers and the poor are those like Jonathan Kay whose complaints take political cues from service to elites.