Here’s a familiar refrain: “Someone’s wages rose faster than someone else’s: report”. This depersonalized version sounds about as cynical as it should especially since the first someone is usually not a CEO whose wages are actually rising faster than everyone else’s – it’s that fat cat across the street, like you know, the garbage collector or maybe the admin assistant at your community centre. Or at least that’s who it is in this case as the headline actually reads, “Municipal employees’ wages rose twice as fast as provincial public sector: report.”

The report in question is one commissioned by the British Columbia government to put pressure on the wages of municipal workers, or even bring centralized bargaining to the still-autonomous municipal sector. The specific claims in the report as well as the shortcomings of its method have been thoroughly debunked by interested parties, both CUPE and the Union of BC Municipalities.

I want to use this as an example of something I seem to come across a lot lately… For beyond the wage comparisons, the economic indicator most prominently referenced in this report is the rate of inflation. More and more, it seems like any wage gain over and above the rate of inflation just isn’t fair. This is not a new argument and it is most easily applied to the public sector that has the stereotype of fat cattery stuck to it. Regardless whether it’s just me noticing it more, it turns out to be an odd one.

The basic problem is that this argument is out of line with the mainstream economic theory to which most of those making it ostensibly subscribe. That not-unfamiliar “go back to Econ 101” argument can be made here against those usually making it. In short, Under a whole array of conditions relating to the competitiveness of markets (perfectly so!) and the structure of production (very particular!), wages should be directly related to labour productivity.

Economics interruption (links to text below, but feel free to skip).

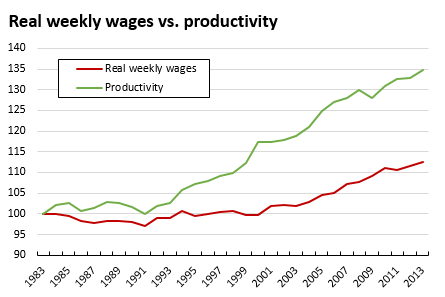

The short of the long is that there is, according to mainstream theory, some fundamental relationship between productivity and wages. What we have witnessed, however, is a grand divergence of wages and productivity. Both in the US and in Canada, looked at in real terms, productivity has grown while wages grown more slowly (or outright stagnated at times):

The fundamental mischaracterization being made in reports like the one cited above is that wages should follow the cost of living: effectively, that workers should not partake in the proceeds from economic growth – that productivity gains should go to the owners (or in this case, to taxpayers as “savings”). Having lost much of the power to effectively bargain for more , we are left with less and the justifications for less are that much easier to make. Indeed, it is sadly no surprise that business and “taxpayer” (more accurately, austerity) pressure groups were the only ones whose input was sought by the authors of this particular study as well as that the resulting mischaracterizations appear uncritically in the mainstream media.

Political interruption (feel free to skip again).

There is a long history in economics of the puzzle that money wages do not often fall, and this fact has been used to explain recession and involuntary unemployment. Our negative psychological reactions to falling numbers are the flip side of Keynes’ “animal spirits” of entrepreneurs who chase after gain – and both find their way into the mainstream framework. Yet allusions that wage growth should be pegged to inflation conflate the psychological concern to maintain adequate money wages with an overriding political concern to fix any distribution of economic gains to workers at the level of the cost of living.

In this way an empirical fact about recent capitalist organization of human labour – the disconnect between wages and productivity – is erroneously turned into an ethical proposition…one that underlies reports like this latest on BC’s municipal workers. In short, workers should be getting a stable wage whose growth matches inflation, with gains that are purely monetary.

This argument boils down to a hard-nosed answer to the question of “who deserves what?” In other words, buried under the rhetoric is a theory of desert that oscillates between the lowest common denominator school – municipal worker wages shouldn’t grow faster than those of other government workers – and the monetary-gains-only school – or at very least not faster than the cost of living. We are told that we deserve wages that keep us at a constant standard of living.

This, however, harkens back to the theory that wages are set to maintain a given level of subsistence, a basic assumption of the classical economists who argued about whether this level was absolute or relative. A wage that increases with inflation but no more is a relative subsistence standard: we get new gadgets but we remain at a steady, culturally-specific “fixed” wage. This is a theory of power; rather than participating in a distribution of gains from economic activity, we give our time up to employers for their gain; in return this year we get an iPhone 6, next year an iPhone 7; this year $14, next year $15 while our social productivity expands at a much faster rate. The argument is easier to make on the basis of public sector workers because it seems, in a cruel irony, that the savings accrue not to employers, but to ourselves…until the same argument is applied to private sector workers as well. Or better yet, since organization is so much lower in the private sector, there is less reason for such ideological attacks as bargaining power is already low.

This notion of relative subsistence may seem a throwback but it is not too far from reality: Statistics Canada recently reported that the average minimum wage has grown by a penny in real terms since 1976. This is what reports like the one on municipal salaries in BC would like to see transpire for all. Castigating some for doing slightly better ends up at the old notion that everyone should be doing equally badly.

Philosophical interruption (the last one).

Interruptions

Clearly this is an over-simplified characterization as there are plenty quibbles to be had:

- What is the actual level of competition and how far do marginal measures diverge from average measures in particular enterprises as well as on average in sectors and economy-wide, especially since average economy-wide productivity commonly appears in graphs like that below?

- In this particular case, one of the difficult questions is how we measure public sector productivity as public sector output is generally not only not sold on the market, but hard to define.

- The past half-century has seen enormous refinement of the mainstream theory to take into account information asymmetry and incompleteness with concepts like efficiency wages, signalling or search and match. Yet these generally offer reasons for why wages should exceed what the basic theory would predict.

The fundamental issue though is the overall established link between productivity and living standards. Here’s Bank of Canada’s backgrounder on productivity:

However, productivity growth is a major source of improvement in our economic well-being in the long run. Gains in productivity allow businesses to pay higher real (inflation-adjusted) wages and still keep costs down and stay profitable and competitive. So, rising productivity is vital to sustained improvements in real incomes and living standards over time.

There are other questions, quite the opposite of the economic type above and more important, that deal with the position of public sector workers in the labour movement. While public sector workers are still heavily unionized and have experienced significant gains in the past, they have both been under attack in very recent history (especially in provinces like BC where many groups have faced so-called “net zero” contracts and contracting out) and yet remain one of the few sectors able to back up bargaining demands with large-scale action (as the recent teachers’ strike showed). A view that would in a blanket fashion cast the public sector as privileged misses both of these: both the non-monolithic nature of a public service being made increasingly precarious and its potential for fight-back.

Matt Bruenig has written on the topic of desert with clarity for quite some time. First, a more exacting theory of desert would likely come to the conclusion that the vast majority of what we produce have its source either in common knowledge passed down from the past and the common resources originating in unimproved nature:

In short, the view that individuals should receive only their marginal product actually generates the conclusion that the substantial part of our national product resulting from inherited technology and knowledge belongs to no living person, or more reasonably to everyone in general.

Going a bit further, there’s a deeper argument against even a simple, coherent notion of productivity-based desert that deserves reflection:

The emphasis on compensating for economic contribution is problematic. This emphasis feeds into right-populist producerist ideologies that regard the poor and unemployed as parasites. Under desert theory, it would seem that unemployed people, the elderly, the disabled, and others would have very little to no entitlement to anything. That’s not a satisfying conclusion.