The New York Times reports that Wall St. is back in a big way since the 2007 crisis: profits, salaries and confidence have returned in the US financial industry. As often happens when I see something intriguing like this about the US, I wanted to quickly see whether a similar dynamic is taking place in Canada. Turns out that Bay St. is doing better than ever too…though it never really went away.

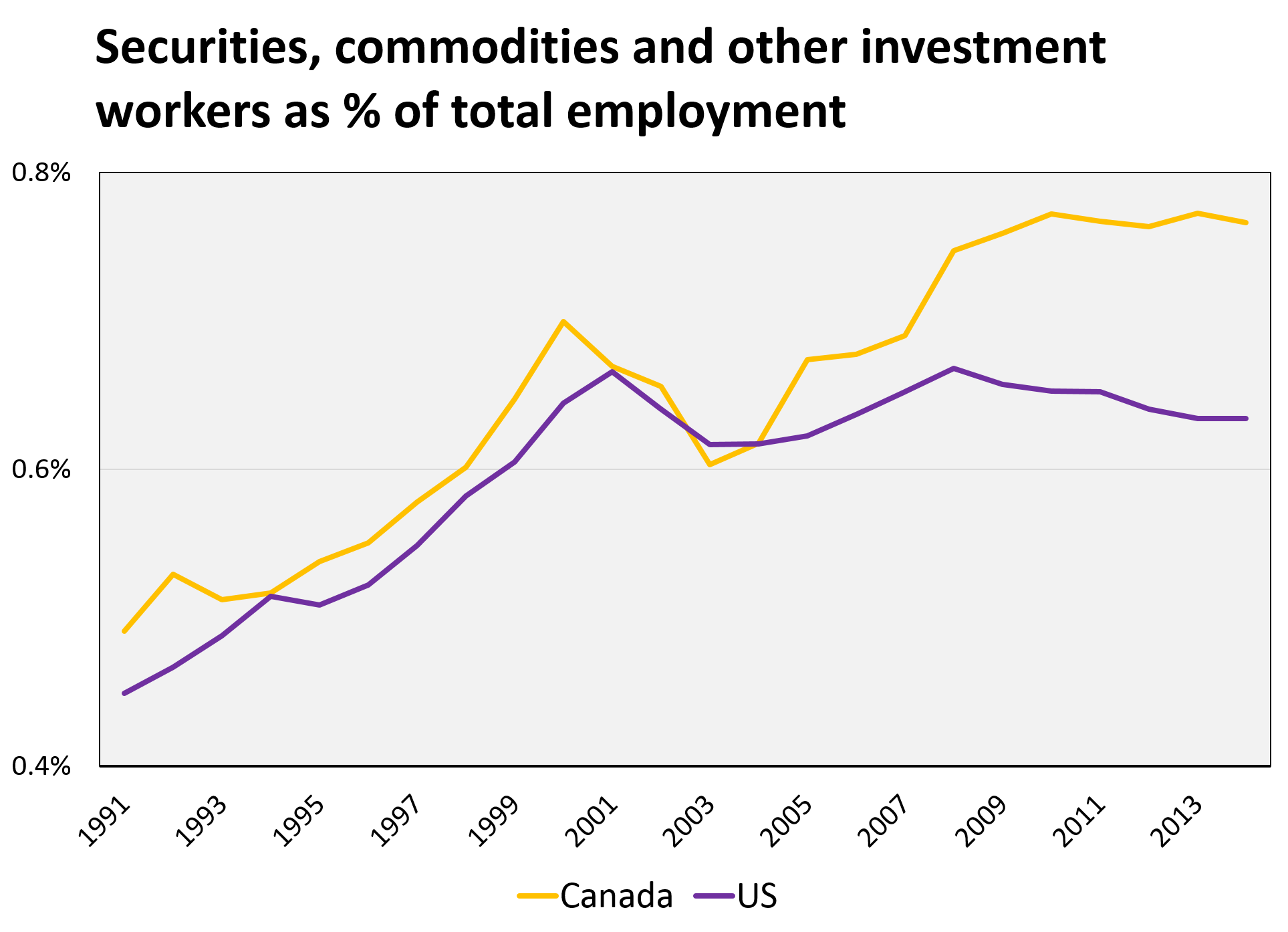

To illustrate this, consider two of the charts used in the Times piece, both augmented with Canadian data. First up, employment in the financial sector. While the US saw the number of securities and investment workers flatline after the crisis, Canada has continued to see more growth, only plateauing more recently. Today a greater percentage of total employment is in the investment subsector than in the US.

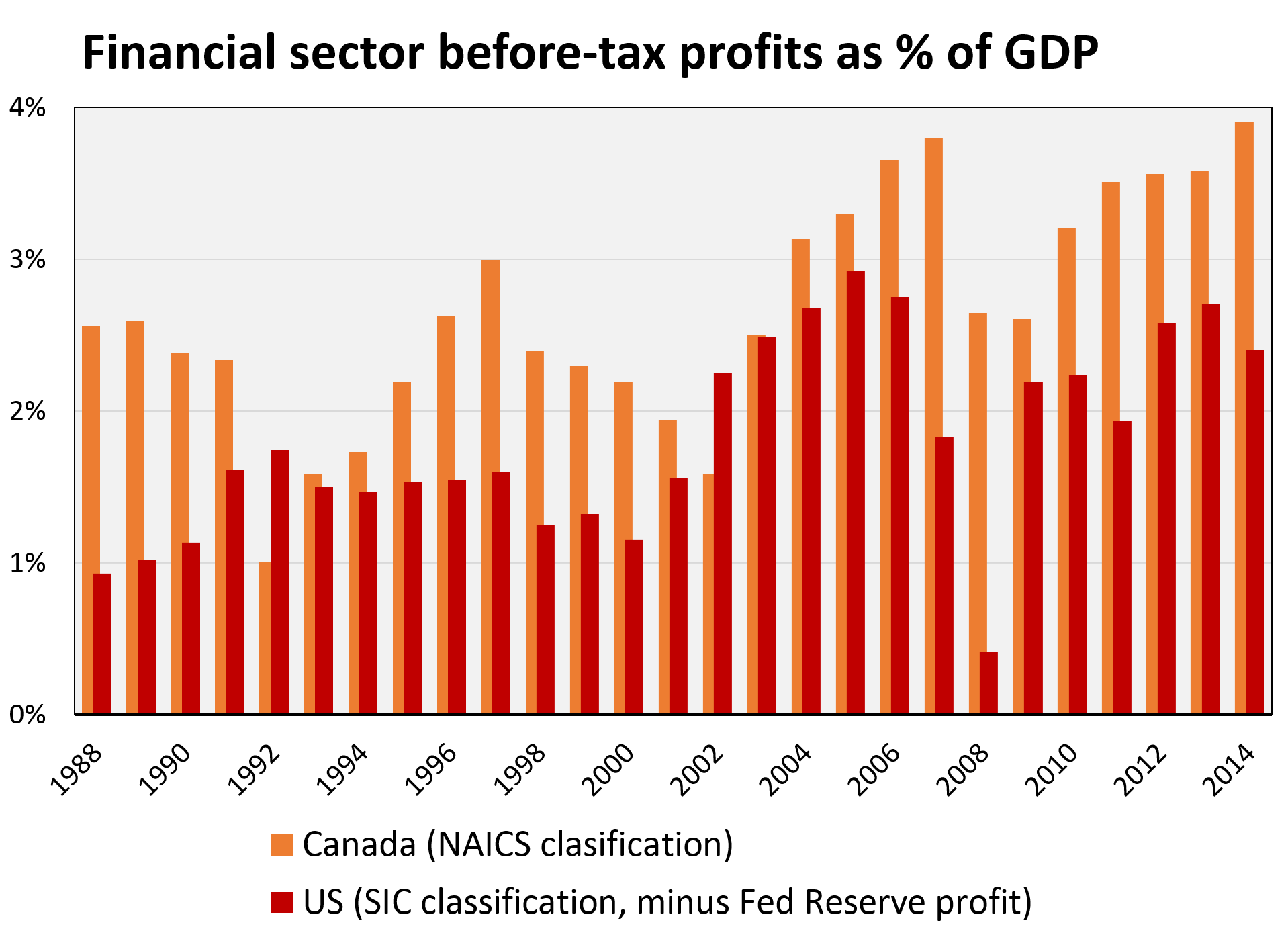

Even more pronounced is the case of financial sector profits. Taken as a percentage of GDP, the mass of Wall St. profits dropped off sharply after the 2007 global crisis. Canada’s mass of financial profits saw a much smaller dip; it’s been much steadier overall.

Two notes about this chart: first, the data come from slightly different classifications, but what is important is the relative level. Second, this is different than the profitability of the financial sector which is measured against the assets, or possibly the sales, of the sector itself.

The last chart featured in the Times shows how much average salaries and wages in investment outpace the economy-wide average (hint: a lot!). I wasn’t able to come up with a good enough counterpart in the Canadian data for the US “full-time equivalent” measure of earnings used by the Times. By one measure, the average Canadian worker in securities and investment still makes over 1.5 times the overall average in base salary. This, however, doesn’t take into account the bonuses, options and other sources of income that make finance such a driver of inequality. These also look like they didn’t suffer the same drop on Bay St. as they did on Wall St. during the immediate post-crisis years.

The crux of the matter is that, by a few measures, Bay St. is a good match for Wall St.; on the other hand, it doesn’t get nearly as bad a rap in the public’s eye as its US counterpart. In part, this is because Canada’s financial elite remains bound by stricter rules and regulations. In part, this could be due to the fact that Bay St. still likely contributes somewhat less to inequality in Canada than does Wall St. to that in the US. Wall St. and London’s City are much larger and mop up the most ambitious financiers. Canada has a banking oligopoly that has found way to prosper in a more “low-key” equilibrium.

There is nothing, however, to suggest that the incentives in high finance are somehow fundamentally different by the shores of Lake Ontario than they are by the Hudson River. In fact, the problem with its better image is that Bay St. is also the subject of less scrutiny. The arguments brought out in the Times piece combined with the rudimentary Canadian data suggest we should pay closer attention.

Of course, the financial sector is indispensable to advanced capitalism; in this sense, we’re stuck with some form of it. However, a large financial sector can still destabilize the economy (just ask the IMF!), eat away at productivity growth in other industries, give rise to accelerating income and wealth inequality as well as more facilitate all sorts of unsavoury elite practices.

Here are a few stories from just the past few weeks:

- The upcoming Hydro One privatization is set to generate large fees (and profits) for Bay St. The financial industry was already hoping for fees in the hundreds of millions last time this privatization was attempted in 2002. Outright privatizations or more stealthy transformations of public services via P3s are a bonanza for finance at the same time as they redistribute ownership claims upwards and weaken what’s left of the welfare state. A larger financial sector has greater capacity to push for these and the short-term gains they generate.

- Just today, five major global banks plead guilty and will pay billions of dollars in fines for fixing global exchange rate markets. This is reminiscent of the LIBOR interest rate fixing scandal that ultimately resulted in huge fines for many global banks last year, including Bay St. giant RBC. Even the more regulated Canadian financial industry can take part in global speculative fraud.

- Increasing amounts of Canadian corporate cash are flowing to tax havens. Aggressive “tax planning” is something of an off-shoot of Bay St., enabled by greater financial specialization and integration. It’s a good example of how the expansion of the financial industry can reverberate across the economy.

Bay St. might not be Wall St., but it shouldn’t be far off the centre of our radar.