It’s relatively common knowledge that employer-run pensions have been scaled back over the past few decades. I’ve decided to dig some data on pensions for this post to see just how this has taken place in Canada, motivated by a just-released analysis of US pension reform that finds contradictions in how US workers have come to take on more and more of the risk for their retirement income.

First, a bit of background. There are two main kinds of employer-administered pension funds: defined benefit (DB) plans – where retirees receive a set monthly income, or defined benefit – and defined contribution (DC) plans – where retirees receive a variable monthly income dependent on how much they proportionately contributed to the pension plan and how this money was invested. There are also completely individualized retirement savings plans such as the RRSP, but these are essentially individuals investment accounts given preferential tax treatment. However, the link between RRSPs and DC plans is that they generally place investment risk on workers themselves; if whatever financial instrument the money is invested in suffers, retirement income also suffers.

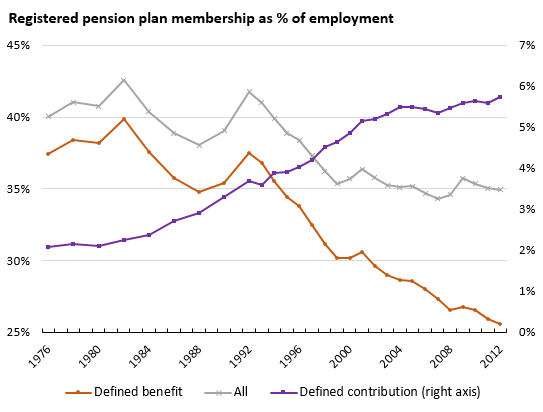

While some employers have eliminated pensions altogether, many have restructured their pension plans. Here’s the Canadian data on registered pension plan membership, plotted as a percentage of employment: