Last week I interviewed Branko Milanovic, one of the world’s foremost authorities on inequality. Our conversation moved freely from global trends in inequality over the past quarter-century to the rise of a new plutocracy and the threat it poses to democratic governance. I thought it worthwhile to transcribe our chat in full.

A bit more about Branko: he is currently a professor at the CUNY Graduate Centre, where he also heads the Luxembourg Income Study Centre. His most recent book is The Haves and the Have-nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality and he has a great blog worth reading. Here is our conversation, edited lightly for clarity and length:

Michal Rozworski: How has global income inequality evolved recently?

Branko Milanovic: Global income inequality is really defined as inequality between individuals. So, in principle, it’s the same as inequality within a country if you were to assume that the world is one country. Surely we have to allow for differences in price levels – that’s really the important difference between inequality and global inequality because price differences between countries in Africa and, say, Norway are enormous and, obviously, we have to allow for the fact that things are much cheaper in Africa.

Having done all of that, the basic story is that, first, the level of global inequality is extremely high. It’s higher than within any one country, which is not surprising. But what is also interesting is that this level, to any extent we can really determine, has been slightly going down over the past ten years approximately. In other words, all the evidence we have points to a downward trend, except that we are unsure if the trend is larger or smaller. The reason for this is that the relatively poor and populous countries, such as China, India, Indonesia, Vietnam and so on, have now had 15 or 20 years of very high growth rates – higher than the rich countries – and they are the ones pushing inequality down.

The final point is that all this happens while inequality in all the countries I mentioned, as well as in the US and Europe, is going up.

You’ve also written about the different trajectories of two middle classes, one in the North broadly, the other in the South, moving closer together because of income stagnation in the North and income growth in the South. How has this worked?

There are really two middle classes: one is the Western middle class and the other is the middle class in emerging economies. What has happened over the last 15 to 20 years is that the Western middle classes have generally had very sluggish or even zero growth. This is true not only for the US, which is quite well-known, but also true for Germany, which is less well-known, and Japan, where there has been stagnation of both wages and real incomes.

On the other hand, you have the emerging middle class, which I have to underline is still much poorer than the middle class in the West, but which also actually had very significant rises in real incomes, more than doubling over the past 25 years. This is especially the case for urban China, but also rural China and other Asian countries. So these two middle classes are becoming more similar because one group is growing while the other group is stagnant. In this sense, we can speak of some kind of global middle class, although I’m not a huge fan of the term because it combines, or mixes up, these two classes that are very different in terms of income.

So speaking of any kind of real levelling is still a ways off.

We speak of a global middle class in a more casual way but the differences are significant. Even people who we in the West perceive as middle class in the poorer countries, like India, are actually in the top 5% of the distribution in their own countries. To just give you an idea: social assistance or the poverty line in most rich countries kicks in at about $15 per day. This is an income level that is fairly high by emerging market standards, where the median income can be at $6 or $7 per day.

What about the very wealthiest in global terms? Is it more fair to speak of a global oligarchy or global really wealthy class that is more similar regardless if it is in Mexico City, the City of London or Shanghai?

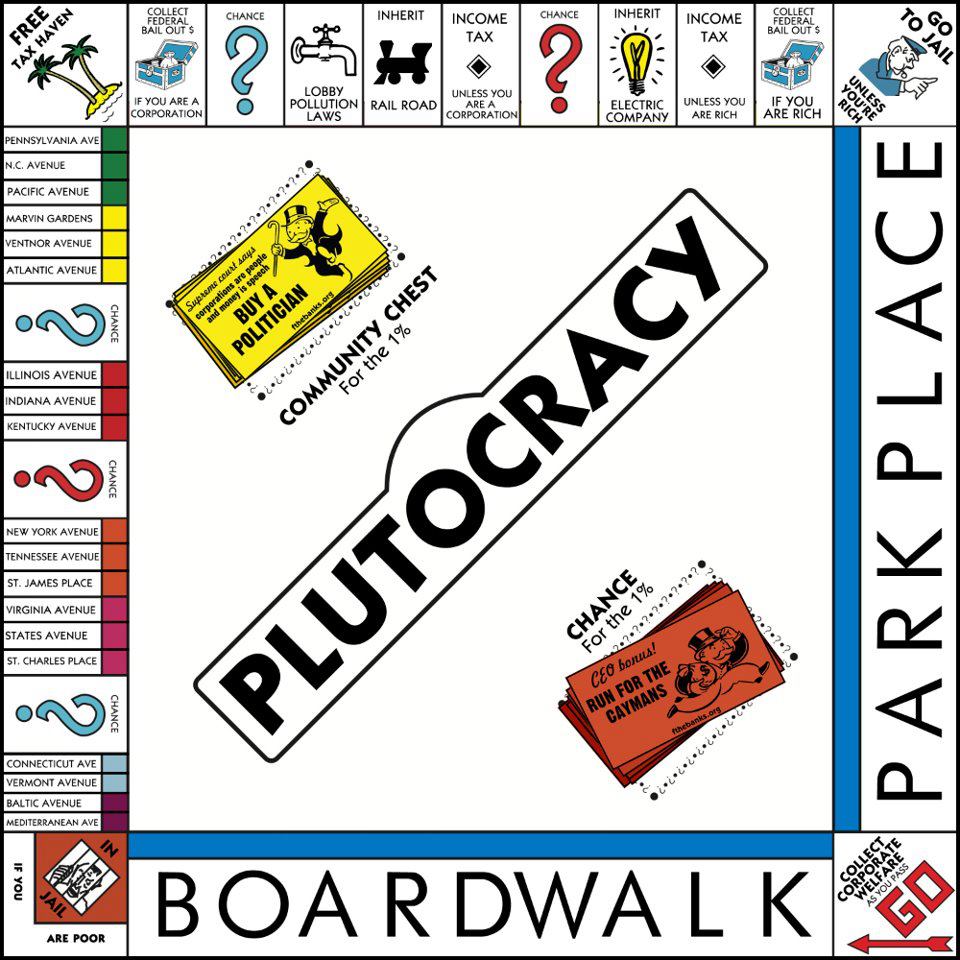

Yes, this is true. The last quarter century is characterized by, at the same time, the emergence of what we just talked about, a global middle class, but also the emergence of some kind of global plutocracy. This is relatively small in percentage terms: these are people who share similar incomes, similar lifestyles and interests and who might live in a dozen metropolises in the world. Even a larger group, say the global 1%, or about 70 million people, has seen significant gains.

Yes, this is true. The last quarter century is characterized by, at the same time, the emergence of what we just talked about, a global middle class, but also the emergence of some kind of global plutocracy. This is relatively small in percentage terms: these are people who share similar incomes, similar lifestyles and interests and who might live in a dozen metropolises in the world. Even a larger group, say the global 1%, or about 70 million people, has seen significant gains.

Essentially what has happened is large increases in real incomes around the middle of the global income distribution, stagnation amongst people who are relatively well-off globally but really middle class in the rich countries and a global plutocracy or global 1% with large increases in real incomes. So that’s a mixed picture of what has happened over the past 25 years.

I really liked a short quote from one of your talks. You said, “we should not only focus on what may be called the ‘Delta Economics’, that is looking only at the changes and forgetting about the levels.” What do we lose when the debate is simply about whether inequality has simply gone up or gone down a bit?

We have become a society very much – perhaps without realizing it fully – fascinated by change. I’m not saying that changes are unimportant; obviously, they are very important. But if you look at the change compared to the level, the changes are always small on an annual basis or even over five years or more, while we tend to forget the massive differences in income levels.

Take the example of China and the US. Of course, we know that China is growing faster and might eventually catch up with the US, even in terms of per capita income, but we forget that the differences between the two countries are very significant in income levels. In PPP (price-parity) terms, they are four to one. We should not become only obsessed with changes.

Even if you look at the global middle class which registered a doubling of its incomes, these real incomes are still small. If you look at where the absolute gains were most important over the past 25 years, they were most important among the rich. This is very simple to explain. If I’m rich and have $1000 per day and I get just a 1% increase, that’s $10. Another person at $10 per day might have a doubling of their income and get the same $10. If we only focus on the percentages, that’s not the full picture.

I think there are important political implications to all of this. It’s one thing that rising inequality has given rise to a new class of plutocrats, but it also gives rise to a kind of vicious circle. This class has not only greater and greater reasons to consolidate its economic gains at the expense of others, but it also has ever greater means to do so.

The danger there – and to some extent I think it’s already materializing – is that economic power, which is often acquired through a combination of political and economic power, tends to be translated more and more into political power. This becomes an attempt and an ability by the rich to design the rules in their own favour and to maintain these rules.

That is what we see at the level of nation-states. We also see it at the global level – although there the governance rules are different – through organizations like the IMF, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization or through informal gatherings like Davos. You essentially have a group of very rich people trying to determine global rules.

Indeed, if you just look people who are extremely rich, not the 1%, but really a select group – billionaires in real income terms over the past 20 years so those worth over $1 billion 20 years ago and closer to $2 billion today to account for price changes – they have gone from owning 4% of global GDP to now 8%. It’s clear the very wealthy have become even richer.

Right, and have the power to continue accumulating wealth.

I think to a large extent they have become even more able to decide on the rules. This is potentially a danger to democracies on a national level, which then become less meaningful. If many of your economic policies are determined externally, then what you decide in your own country is not that much. Plus there are the global rules…

I think we saw that in the global South, but are now seeing it more in the North as well, for instance in the European Union, where the external rules determine a lot about a country’s room for movement.

What has also become clear is that a sharper division between the North and the South is being blurred. It’s partly being blurred because the South is becoming richer and in some ways catching up with the North, but also because political systems are becoming, to some extent, more similar. It’s not, for example, evident that money plays less of a role in the US than South Africa. In other words, what used to be called “political capitalism” has become more prevalent in the older democratic countries.

One reply on “Branko Milanovic on inequality and the new global plutocracy”

All this talk about plutocracies via “political capitalism”, yet not one mention about how the control and manipulation of fiat currencies has created the largest financial banking scam in the history of mankind, allowing an elite ruling class to become super wealthy while the working masses bear the burden of the perpetually increasing debt incurred by the scam. This economic scam is the primary cultivator of plutocracies.

A paramount fact which collectivists apparently refuse to acknowledge is that “capitalism” really means “free market”, of which there are none in the entire world besides the unregulated black market. Whenever a government imposes regulations upon the otherwise free market, the market is no longer “free”, and therefore cannot accurately be called “Capitalism”.

“Equality” should have absolutely nothing to do with the redistribution of wealth, as collectivists routinely assert. Rather, it should have everything to do with ensuring the unalienable Natural Rights of the individual has equal protection under the rule of law.

In such a legal construct where the STATE performs its proper function in a free society, peace, prosperity, and liberty will be maximized. By contrast, when the STATE allows — or itself commits — violations of Natural Rights (such as interfering with the otherwise free market), turmoil, poverty, and tyranny is maximized.

Natural Rights Coalition — Principles

https://sites.google.com/site/naturalrightscoalitionsites/principles