I wrote up the Conservatives’ new balanced budget law for Ricochet. In short, the law is really silly in terms of economics, but simply pointing out its economic stupidity is not enough, because the whole point is to shift the political consensus. Politically, it’s not that dumb. So rather than play games about who cut better and balanced budgets faster as many are doing, we need to look at the balance of economic power that drives these moves. The full piece is below:

The Conservative government’s balanced budget legislation is a classic attempt to shift the boundaries of acceptable public debate. In terms of economics, it is a silly exercise in arbitrary rule-making and its rules are bound to be broken. In terms of politics, it is another step in consolidating a consensus that puts punitive cuts to the many in the service of ever-larger gains for the wealthy few.

The legislation set to be introduced by the federal Conservatives along with the upcoming budget has been attacked as myopic and the result of twisted logic. Pundits left and right agree that the legislation will be unenforceable and thus unsuccessful in the long run. The problem with the law, however, is the already visible success of those pushing Canadian politics wholesale to the right.

While details are still scant, the legislation aims to force subsequent federal governments to refrain from deficit spending except in as-yet-undefined “exceptional circumstances.”

While details are still scant, the legislation aims to force subsequent federal governments to refrain from deficit spending except in as-yet-undefined “exceptional circumstances.”

We’ve seen this movie before. In Canada’s largest province, Ontario premier Mike Harris introduced balanced budget legislation only to have it repealed in 2004 and replaced with a softer version that does not stipulate outright balance every year. Most Canadian provinces have balanced budget legislation, but not surprisingly all suspended it at some point in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008.

Even the Eurozone, the current poster child for austerity, has a limit on national government deficits (equal to 3 per cent of GDP) rather than a ban on them. Like other rules of this type, though, the number itself is not as important as the lack of flexibility and the push for spending cuts as the default response to crisis. The Eurozone rule has certainly contributed to Europe’s inability to escape stagnation and prolonged crisis since the financial crash — despite being broken by various countries, largely those powerful enough to get away with it.

Arguments like these, however, do not get at the heart of the matter. It’s good to have a few of them out there, but balanced budget legislation is most dangerous not because it’s bad economics, but because it is good politics.

Who cut more?

Balanced budget legislation is a perfect example of how elites have been able to shift the framing of political debate rightwards. Sticking to just the arguments and examples above, we are playing the game without seeing that the goalposts have shifted by a country mile. At its worst, balanced budget legislation invites a game of who cut more and who cut better. Many Liberals have already taken the bait.

Joe Oliver (or any Conservative) has a lot of nerve lecturing #LPC about balanced budgets, illustrated. #cdnpoli pic.twitter.com/T3gQuLDZmx

— Gerald Butts (@gmbutts) April 8, 2015

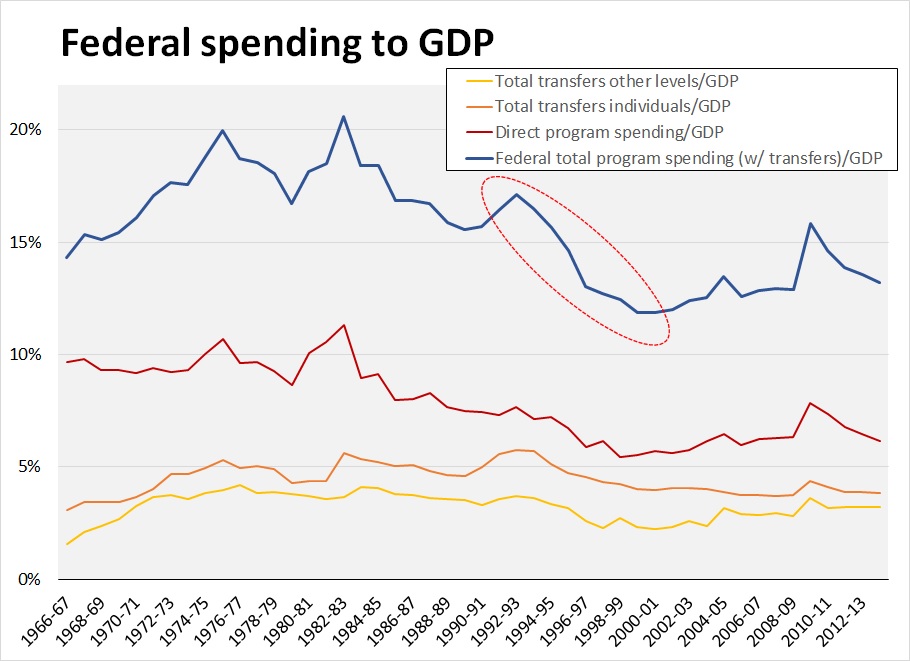

Here’s what the chart in the tweet linked above amounted to in the simplest terms if we separate out the two components of what makes for the budget balance: spending and revenues. Those surpluses starting in the late 1990s were bought with massive cuts to direct program spending, transfers to provinces and transfers to individuals:

Liberal governments in the 1990s kick-started the current long-standing cycle of Canadian austerity, but the framing of balanced budget debate turn it into something laudable. Just looking at the budget balance — that is, revenue minus spending — misses what happens to its two components taken separately. A massive new social program or infrastructure build-out coupled with higher revenues can have the same impact as a massive cut to social programs plus a tax cut. What’s more, additional revenues today could be drawn disproportionately from the wealthy who have seen their wealth and incomes rise, due in part to tax cuts under Liberals and Conservatives that have recently disproportionately flowed to the wealthy.

The balance of power

But even these arguments about spending are still a part of the same game. If we really want to move the goalposts rather than move within them, we have to think further. And the more we move away from the balanced budget game, the closer we move to economic power.

The conflict over the size of the government budget is to a large extent that over the size of the social wage — the array of services such as health, education, and housing that complement household wages earned at work. The past two decades have seen both the working and social wage squeezed: the former largely stagnant, the latter slowly falling.

Balanced budget legislation theoretically says nothing about how big the budget should be, but in practice it is part of an attack on the livelihoods of the many to the benefit of the few. It aims to squeeze the social wage further.

Austerity and balanced budgets in a time of slow growth or stagnation squeeze the 99% and give the 1% more power to exact further gains for themselves. At the same time, loose monetary policy around the world is largely fueling rentier capitalism rather than investment. The 1% are able to squeeze the maximum money gains out of enterprises via dividends, share buybacks and asset price inflation rather than allowing firms to invest. While fiscal and monetary policy across most of the rich countries seem to be working in opposite directions, both public and private investment are stalled.

Balanced budget legislation and a more general lack of expansionary fiscal policy in this situation is not due to the wrong-headedness of elites but instead flows directly out of their interests. As such, an appeal to simple Keynesian counter-cyclical spending means little with the goalposts where they are. Remember that Keynes sought the “euthanasia of the rentier” — a transfer of power, not just a stabilized economy.

Rather than argue about who can fare better at the balanced budget game, we need to rebuild coalitions and campaigns that can really take on elites, not just win at their silly games.

Balanced budget legislation is thus but a symptom of a greater malaise. Economically, it is a red herring, quickly done away with whenever exigencies demand. Politically, however, it is one more step forward by elites that needs to matched by many more steps of the 99% in the opposite direction.

One reply on “The Conservatives’ balanced budget legislation: Silly economics, smart politics”

The other big concern I have with the way in which Conservatives manage our budgets is the ‘shell game’ they play with our money. Jim Flaherty was an expert with shuffling money under the mattresses of various departments, only to demand the money back when he had to pretend they were going to create a ‘surplus’ so they could say ‘look at us and how great we are at managing the country’s budget’. Joe Oliver is no different.

The result of this is that you get chronic under-funding of organizations and federal departments, whereas transfers to oil companies and defense contractors are expedited.

You are correct with your summary: a Conservative budget has nothing to do with economics, but everything to do with politics.

I can’t wait to see what destruction they will bring with their new ‘omnibus’ budget. If it ever comes.