This is the third and final post in what has become a three-part series on the puzzle of high profitability and low investment in the Canadian economy. In the first part, I looked at some data that shows the existence of the puzzle and explored a few of the factors that could be behind it. The follow-up post outlined broadly Keynesian and Marxian solutions aimed at raising investment: the former based on stimulating demand, the latter on eliminating overcapacity and increasing the relative profitability of productive capital. Here, I want to continue the thoughts that concluded the second part, namely that the Harper government’s preferred response to the puzzle has been neither demand stimulation nor industrial policy. Instead, it has been austerity – a strategy by no means accidental, but in fact designed to support the status quo of high profitability and low investment.

Austerity is not an isolated Canadian phenomenon nor is it a new one. The neoliberal era that began sometime in the 1970s has seen austerity in one form or another applied worldwide. Economic crises have especially provided governments with excuses to institute or continue austerity policies that would not have been difficult to institute otherwise. While Canada did not experience the latest economic crisis to the same extent as a number of other countries, it has seen a more moderate version of many of the same trends – such as slower growth and lower employment. The crisis was large enough to allow the Harper government to continue and deepen a tentative austerity regime. While Canada has not pursued austerity programs as spectacular as some, for example the UK or Spain, the Conservative government has, nevertheless, succeeded in substantially reducing the size of government, small cut by small cut. While Canadian austerity policies predate the crisis, the crisis has only helped to entrench them and further orient them towards propping up profitability.

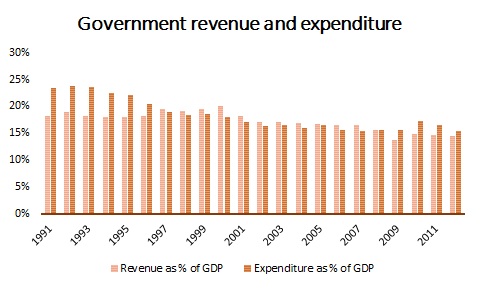

For over two decades, Canadian government expenditures have been falling steadily as programs and thousands of public service jobs have been cut across departments.

Figure 1. Falling Canadian government revenues and expenditures since 1991. Source: Statistics Canada.

Figure 1. Falling Canadian government revenues and expenditures since 1991. Source: Statistics Canada.

The drop in expenditures has allowed the government to cut revenues at the same time and still remain within striking distance of the neoliberal imperative for balanced budgets. Although a number of taxes have been cut, the most stunning has been the fall in corporate tax rates – from 28% in 2000 to a paltry 15% at present. Despite this enormous tax break as well as significant cuts to government spending and income and a forecast to balance the books by 2015, austerity has done little to stimulate private sector investment. The government “getting out of the way” of the private sector has simply left a great big hole that business seems to have no intention of filling. There is, however, a method to this madness.

When Jim Flaherty claims that austerity is working, he is telling the truth. The inaccuracy appears when he says that austerity is working because it has kept Canada from experiencing a more significant economic downturn. Austerity, as so many commentators have pointed out, has failed utterly in its stated aims of reviving growth, investment and employment everywhere it has been applied. It has succeed in accomplishing other goals. In the most crisis-ridden countries like Greece and Portugal, austerity has allowed governments to keep paying their creditors even as the population is driven closer and closer to the brink of abject poverty. In Canada, on the other hand, austerity has allowed the corporate sector to maintain high profitability without investing or expanding stable employment.

For the corporate sector, the proposition is a pretty good one: if the government can help us maintain high profits without renewed investment, then why bother investing? Indeed, investment is a risky undertaking. Austerity, on the other hand, is a sure-fire strategy for transferring wealth upwards and risk downwards in the income distribution. There are myriad mechanisms at work to effect this redistribution.

Take corporate tax cuts for instance. These are in reality tax cuts for the rich who (predominantly) own corporations. With lower taxes, corporations have extra cash to pay out higher dividends or invest in a variety of financial assets, including stocks and real estate (remember, there is no need to invest in productive capacity!). These assets are, again, largely owned by the rich and it is they who have the most to gain from higher asset prices. In addition, there is no need to worry about the inevitable correction or crash, as recent history shows that corporations, banks and the wealthy will be bailed out by governments. And when the dust settles, they will be the ones with enough left over to buy up the few assets that the now-poorer middle class and poor will be selling off to make it through.

Cuts to government services, on the other hand, can make space for the private sector to provide some of these same slashed services. The transfer of wealth can occur outright via privatization or indirectly, as when private companies fill the gaps left behind when the government stops providing a service. These mechanisms and others amount to the same neoliberal story of privatizing gains and socializing risks and losses.

It is telling which department and agencies are not subject to budget cuts. For example, the CSEC, Canada’s high-tech spy network, is receiving more funds than forecast. This increase, however, makes perfect sense in light of the recent revelations that Canada is conducting widespread economic espionage – targeting, amongst others, the Brazilian government. Why risk the little investment there is in uncertain ventures when you can get the government to spy for you and rig the game in your favour? Although not directly part of the austerity agenda, this is yet another example of government helping to sustain the high profit, low investment status quo.

The strategy of maintaining high profitability and low investment via austerity also has effects on the majority of the population through (un)employment and debt loads. With low investment, fewer jobs – and even fewer good jobs – are being created. While the official unemployment rate has fallen since the depths of the crisis, at 7.2% it remains higher than it has been most of the past decade. However, taking into account underemployment and discouraged workers, this official unemployment rate is off by roughly a factor of two. Meanwhile, the employment rate, or the percentage of Canadians who do hold a job, fell off sharply after the crisis and has not recovered; it is the same as it was a decade ago and much lower than at its recent peak. Of the jobs that are being created, the vast majority are in the lowest-paid occupations, often precarious, and many of them are also part-time – another way that risks are socialized.

Government austerity also means that everyone pitches in and takes on debt to keep profitability high. Canadian household debt has kept up its rapid growth throughout the crisis and its aftermath. It now stands at 95% of GDP, higher than in both the US and the UK. Meanwhile, corporate debt has fallen from above 60% of GDP in 1990 to just over 50% today. Add to this the explosion of corporate cash holdings and it turns out that Canadian companies have the safety cushion and rainy-day fund that most Canadian families lack. Household debt rather than rising incomes brought about by productivity-enhancing investment is fuelling consumption and, to an extent, rising asset prices. When things go wrong – and in this unsustainable model they inevitably do – the result for many middle- and lower-income Canadians will be financial hardship and higher unemployment.

As noted at the beginning, the Harper government has chosen to follow neither demand stimulation nor industrial policy to solve the problem of slumping investment. Instead, it has pursued austerity, helping maintain corporate profits through a variety of mechanisms that impact on everything from government services to household debt to employment. Government discipline in the name of austerity has produced other kinds of discipline for households: the discipline of precarious work or, worse, the unemployment line, the discipline of debt repayment and, ultimately if necessary, the discipline of the dwindling welfare cheque. Investment can remain in a slump because the private sector is let off the hook – not by chance, but by design.

4 replies on “Austerity and the profitability puzzle: government gives profits a helping hand”

The role of government in a crisis is to ensure that the people who caused the crisis aren’t the ones who pay for it.

There’s the one sentence summary I was looking for! Sometimes i wonder if the 1000+ words could have been spared… Thanks Jim.

[…] Political Eh-conomy Left economic analysis from the Unceded Coast Salish Territories « Austerity and the profitability puzzle: government gives profits a helping hand […]

You are welcome Michal. Excellent blog you’ve got.