While it is a truism that migrant labour built Canada, this same migrant labour has long been used to discipline domestic workers. Both facts are imprinted into the history of Canada. Today is no different and the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) is at the centre of debates about migrant labour. Often missing from the debate are the deep links between labour policy, (im)migration policy and the ways these interact to undermine the power and solidarity of workers.

The TFWP has become a lightning rod of criticism as details emerge of the private sector hiring temporary foreign workers (TFWs) for non-specialized service jobs or in situations where Canadian residents were able to take on the work. Corporations from Tim Horton’s to McDonald’s have been exposed for hiring TFWs in front-line positions; these reported incidents point to broader trends.

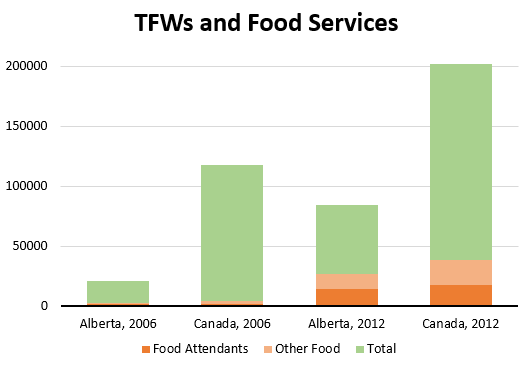

Indeed, while the government has been trying to play these off as a few bad apples finding their way through the regulatory sieve, in reality these “excesses” conform well to existing norms. To wit, the job category “Food Counter Attendants, Kitchen Helpers and Related Occupations” did not even crack the top 20 of TFWP permits issued in 2005. It has, however, rapidly gained in importance as the TFWP has expanded. The category was in 11th place in 2006, was within the top 5 starting in 2007 and overtook 1st place by 2012 (last year of complete data).

Even more telling, while food attendants made up 9% of all TFW Labour Market Opinions (LMOs) issued in Canada in 2012, they comprised 17%, or almost double, of TFW LMOs in Alberta, the province that has the tightest labour market. Indeed, in Alberta the top five occupations filled by TFWs are all in services. For a program that is meant to help employers find workers for otherwise impossible-to-fill positions, it seems to be doing quite the opposite: helping employers staff low-wage service occupations that are relatively always in demand. Government documents show as much – Alberta employers were applying for low-level service LMOs in the same jurisdictions where unemployed workers with skills for those occupations were on EI.

Employers are using TFWs to enforce discipline especially at the lower end of the job market. Increasing bifurcation between low- and high-wage jobs means that the effect is potentially all the greater. The increase in TFWs can be seen as a new tactic in a much broader strategy of on-going labour market restructuring. This includes limits on collective bargaining, measures to make labour more flexible and precarious, as well as immigration policy.

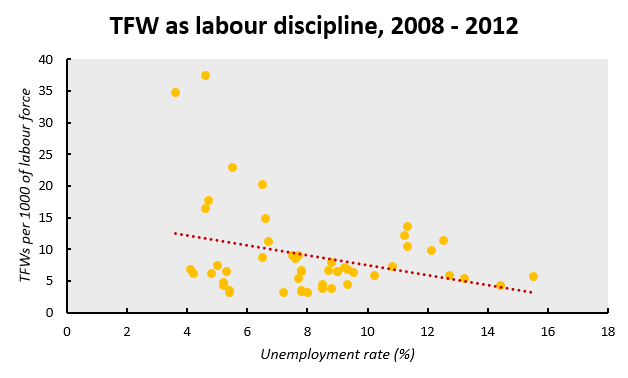

In the above graph each point is a province between 2008 and 2012 – the period since the financial crisis during which Canada saw both an expansion and (somewhat of) a contraction in unemployment. It is also a period during which the TFWP was in full swing. The data appears to conform to the standard economic account. It shows some moderate correlation: data points with lower unemployment rates are linked with greater numbers of TFW permits granted to fill gaps. Yet this story does not fit with the facts that low-wage TFWs are being systematically hired even when there are domestic workers searching for the same positions.

This points to a better reading of this same data: labour discipline. Bringing in more TFWs is one more means of ensuring that a tighter labour market does not lead to increased agitation for better pay and better conditions. When unemployment (and the even greater underemployment) starts to fall, the increased use of temporary foreign workers is a means of securing continued economic power. The cruel irony is that temporary foreign workers hoping to counteract the effects of an unequal global distribution of goods and power on their families are being used to help safeguard and enlarge disparities in their new home.

The different rules for temporary foreign workers – their institutionalized precarity – help spread a lighter but still increasing precarity throughout the rest of the lower-wage workforce. This is enough to condemn the TFWP as a policy tool that stacks the hand of employers in broader labour relations.

The particular genius of the TFWP, especially as applied to low-wage work, goes further. The TFWP is not only a labour policy tool but, at the same time, an immigration program and, as such, interacts with existing prejudices that limit solidarity along the axis of immigration and race. These work to counteract the potential for solidarity that arises from shared experiences of deteriorating labour conditions. The function of the TFWP on the labour market and on immigration should not be analyzed in isolation. The program lies at a problematic but potentially fruitful intersection of class and immigration – by and large meaning at the intersection of class and race. I’ll have a follow-up, hopefully tomorrow, on the links between the TFWP, broader immigration trends and the networks of solidarity that can be used to turn this divide-and-conquer strategy upon itself.

UPDATE: Part 2, The Temporary Foreign Worker Program and labour solidarity, is up.

8 replies on “The Temporary Foreign Workers Program and labour market discipline”

Reblogged this on Old unionist.

[…] The Temporary Foreign Workers Program and labour market discipline April 16, 2014 […]

[…] Want to read more about Temporary Foreign Workers? Check out Michal Rozworski’s “The Temporary Foreign Workers Program and labour market discipline“ […]

[…] Want to read more about Temporary Foreign Workers?Check out Michal Rozworski’s “The Temporary Foreign Workers Program and labour market discipline“ […]

[…] Want to read more about Temporary Foreign Workers?Check out Michal Rozworski’s “The Temporary Foreign Workers Program and labour market discipline“ […]

[…] Want to read more about Temporary Foreign Workers?Check out Michal Rozworski’s “The Temporary Foreign Workers Program and labour market discipline“ […]

[…] The Temporary Foreign Workers Program and labour market discipline April 16, 2014 […]

[…] labour (largely from the global South) – the latter is effectively indentured labour that puts some brakes on even more explosive wage […]