Yesterday, I took a look at the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and how it helps enforce labour discipline on all workers, and low-wage workers in particular. Today, I want to explore the migration side of the migrant worker equation. The context of migration not only makes it easier for employers to exploit TFWs, it also serves to obscure the common core of labour solidarity that should be at the basis of responses to the greater labour discipline that the TFWP enables.

Category: Canada

While it is a truism that migrant labour built Canada, this same migrant labour has long been used to discipline domestic workers. Both facts are imprinted into the history of Canada. Today is no different and the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) is at the centre of debates about migrant labour. Often missing from the debate are the deep links between labour policy, (im)migration policy and the ways these interact to undermine the power and solidarity of workers.

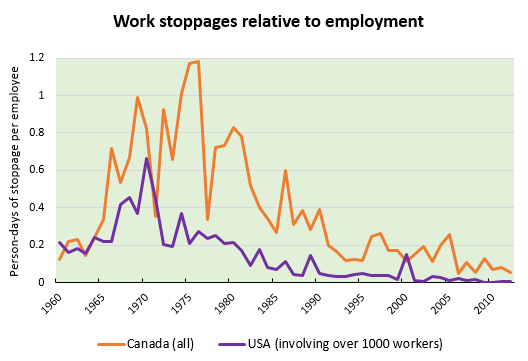

Looking at the prevalence of strikes in the US over the past six decades, Doug Henwood writes,

Second Amendment fetishism aside, there’s an old saying that the working class’s ultimate weapon is withholding labor through slowdowns and strikes. By that measure, the U.S. working class has been effectively disarmed since the 1980s.

Doug then produces a graph showing a precipitous decline in the number of strikes in the US involving more than 1000 workers starting about three decades ago. Intrigued, two thoughts quickly crossed my mind. First, as is often the case, I wanted to see whether the same trend holds for Canada. Second, I was curious whether the decline had anything to do with the large scale of the strikes in the data Doug used.

Sure enough, the conclusions are (sadly) the expected ones: Canada exhibits the same trend and shows it to be one that is independent of the number of employees striking or locked out.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | Email | Google Podcasts | RSS | More

This week’s podcast takes on government economic policy.

First, Armine Yalnizyan looks back at the tenure of Jim Flaherty as federal Finance Minister; the interview is based on an article she recently published in the Globe and Mail. Armine is a senoir economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. She is also a founding member of the Globe and Mail’s Economy Lab feature and the Progressive Economics Forum. You can find her on Twitter @ArmineYalnizyan.

I then talk to Eve-Lyne Couturier about the legacy of the last PQ government in Quebec and the economic debates going into the upcoming provincial election. Eve-Lyne is a researcher at the Institute de recherche et d’informations socio-economiques (IRIS). IRIS produces consistently excellent economic analysis (not only on Quebec) and is far too little known in the rest of Canada.

Alright, so the title is a bit of a cheap hook, taking advantage of the popularity of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century. In his book, French economist Piketty traces the contours of global inequalities of wealth (and income) over the past 300 years and wraps them in a novel and thought-provoking theory of economic dynamics. Inspired by this general theme, I present here a smattering of numbers and thoughts on the links between inequality in Canada and the concentration of hydrocarbon (oil and natural gas) resources.

Piketty mentions Canada several times and only fairly incidentally. On initially flipping through the book, however, I came upon a short section tucked away in one of the last chapters. The section is titled “The Redistribution of Petroleum Rents” and it has some very direct relevance for Canada. In it, Piketty writes,

When it comes to regulating global capitalism and the inequalities it generates, the geographic distribution of natural resources and especially of “petroleum rents” constitutes a special problem.

The remaining page and a half of this very short section is taken up with Piketty’s musings on the two most recent Iraq wars, on the injustices that can develop in petro-states and on how conflict over unequally-distributed of oil can differ from democratic ideals.

The general “special problem” of petroleum rents, however, also applies to Canada. Canada is an interesting case because oil (among other resources) is geographically very unequally distributed within its national borders. Overlaying the unequal geographic distribution is a federation in which provincial governments operate within the same very broad institutional bounds but can yet differ substantially on policy in a wide range of areas. Indeed, Canadian provinces are sometimes compared, in their powers, more to very delimited states than sub-national jurisdictions.

The Toronto Star just published an article I wrote in response to claims made by the Fraser Institute and the Toronto Sun that Ontario has a runaway debt problem worse than California’s.

The short version: I call BS. The slightly longer version: California has constraints, such as limits on the size of debt and difficulties in raising new taxes, that have severely hampered its ability to take on and manage debt. It has a smaller debt than Ontario on all measures but much worse credit standing. Ontario, on the other hand, still has a lot of flexibility to deal with debt. The “solutions” proposed along the Fraser Institute’s alarmism actually seek to create similar, harmful constraints in Ontario. “There is no alternative” becomes true only if we allow alternatives to be removed.

Read the full piece here.

I stumbled upon a presentation released by the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) yesterday. The presentation outlined strategies for companies to integrate ethical and environmental concerns raised by consumers. In many ways, this is nothing new. The distance between this rather tepid advice and the actual needs of facing our economy and our planet brought to mind another gulf that will likely be need to be bridged first: that between public ownership and public aims.

The BDC is a Crown corporation that provides financial services. In short, it is a public bank, an institution of socialized finance. It is a good example of how the reality of socialized finance differs from its potential – of the limits of public ownership that exists without a broader context of democratic pressures for public aims.

I wrote a piece on the very recent proposal to increase the minimum wage in British Columbia that was published over the weekend in The Tyee:

The B.C. Federation of Labour has just proposed to increase the minimum wage in British Columbia to $13 per hour. In short, it’s about time. With this proposal, B.C. joins the minimum wage debate that has erupted across North America. The debate is much needed: poverty wages have no place in today’s economy.

From political proposals to street protests, unpaid internships have been making news in Canada. Rightfully so, as there is a litany of problems with unpaid internships. For individuals, unpaid internships can not only be a form of outright wage theft, they also help entrench class-based privilege that allows some the luxury of forgo income in exchange for work experience. Unpaid internships also distort the labour market and contribute to lower participation and higher unemployment, especially among young workers. For firms, of course, unpaid internships offer some real cost savings. There could, however, be another reason why unpaid internships are popular: they help remake the terms of the labour market itself.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | Email | Google Podcasts | RSS | More

Introducing the Political Eh-conomy Radio podcast, a new podcast on economic issues in Canada and beyond. The inaugural episode tackles postal banking: why cut valuable services and jobs at Canada Post when it is instead possible to create financial services run by the post office, at the same ensuring the Post’s future sustainability? Canada Post put it best in its secret report: postal banking is a “win-win” – unless of course your aim is to dismantle public services and set the stage for privatization.

Interviews include John Anderson, author of the CCPA report, Why Canada Needs Postal Banking, George Floresco, Vice-President of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers and David Bush, who is among those spearheading community organizing to stop the cuts at Canada Post.