Surprise! A new investigation by the Toronto Star and the CBC found that recent treaties with tax havens like the Bahamas and Panama aimed at more “transparency” have just made it easier for corporations to evade ever more taxes. And Canadian corporations have obliged this golden opportunity. “Investment” abroad has ballooned all the while the taps on actual investment at home have run dry.

Signed under Stephen Harper and left untouched under Trudeau, Tax Information Exchange Agreements (or TIEAs) allow corporations to funnel profits through notoriously low-tax jurisdictions. For example, if a corporation only has an office in, say, Panama (of Panama Papers fame), it can pay zero taxes on profits and have the option to repatriate the money back to Canada tax-free. Here’s how the Star report describes it:

“TIEAs are a well-meaning but failed idea,” said Arthur Cockfield, a professor of tax law at Queen’s University who warned the government of the TIEAs potential for abuse.

“I don’t blame the companies. It’s kind of like a Christmas present sitting under the tree. What are you going to do, not open it?”

…Many of the leading corporations on the Toronto Stock Exchange now have a presence in tax havens and use Canada’s treaties to dramatically reduce their tax bill at home. One company, Gildan, reduced its taxes by more than 90 per cent in 2015 (see sidebar).

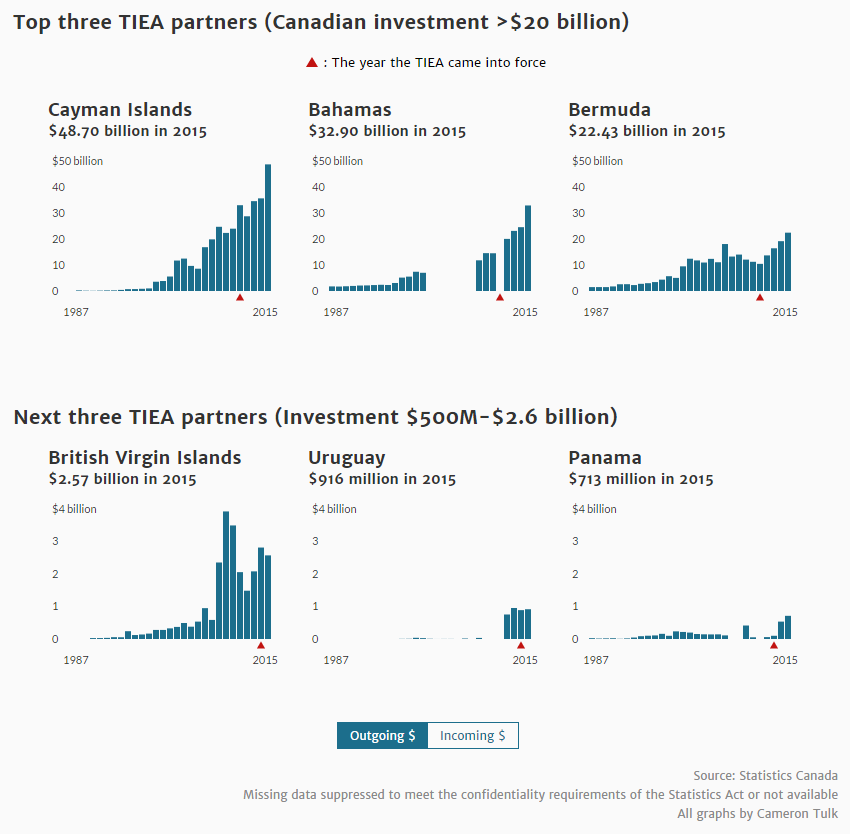

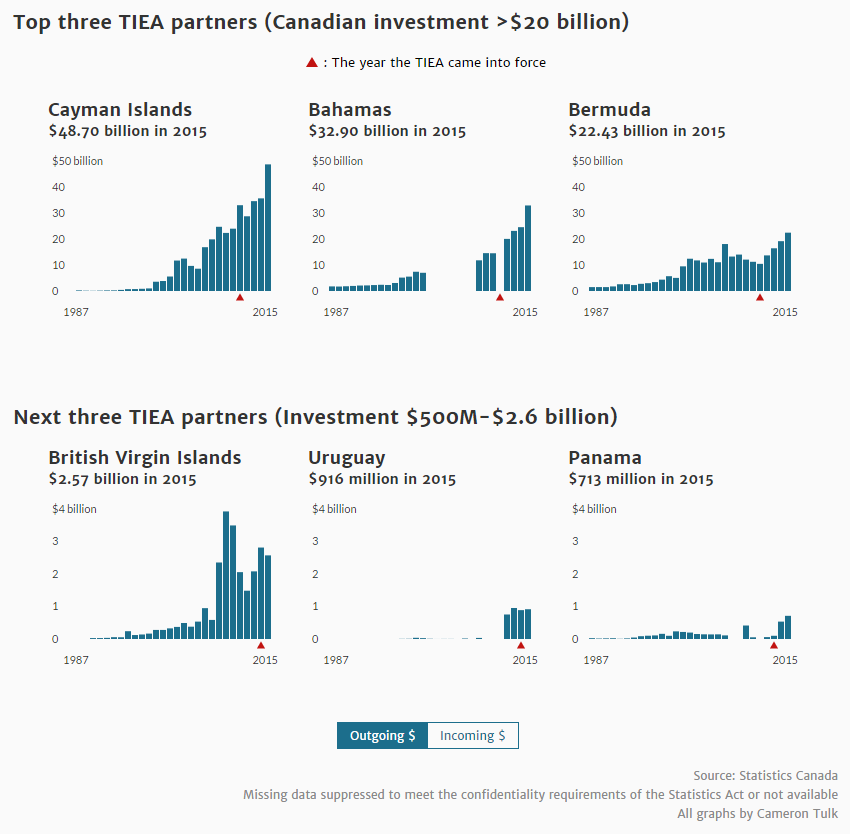

TIEAs have had a dramatic effect on offshore investment, and Canadian money stashed in tax havens is piling up rapidly.

Compare data on foreign direct investment in six major tax havens with charts showing a few measures of investment at home. Here’s “investment” abroad growing rapidly…

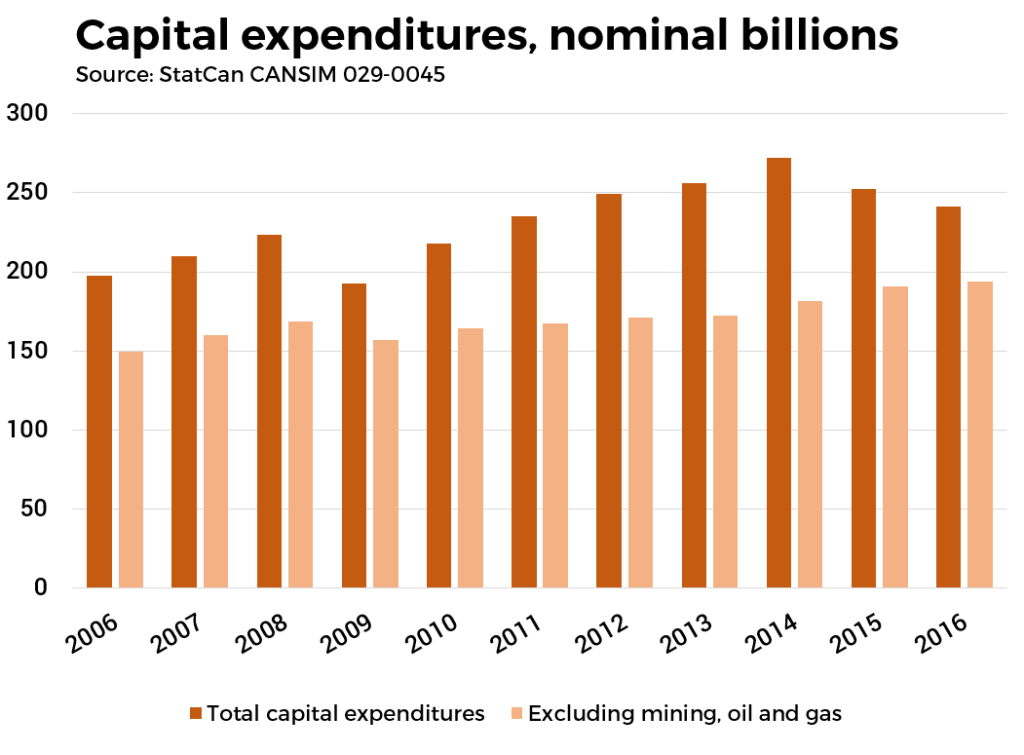

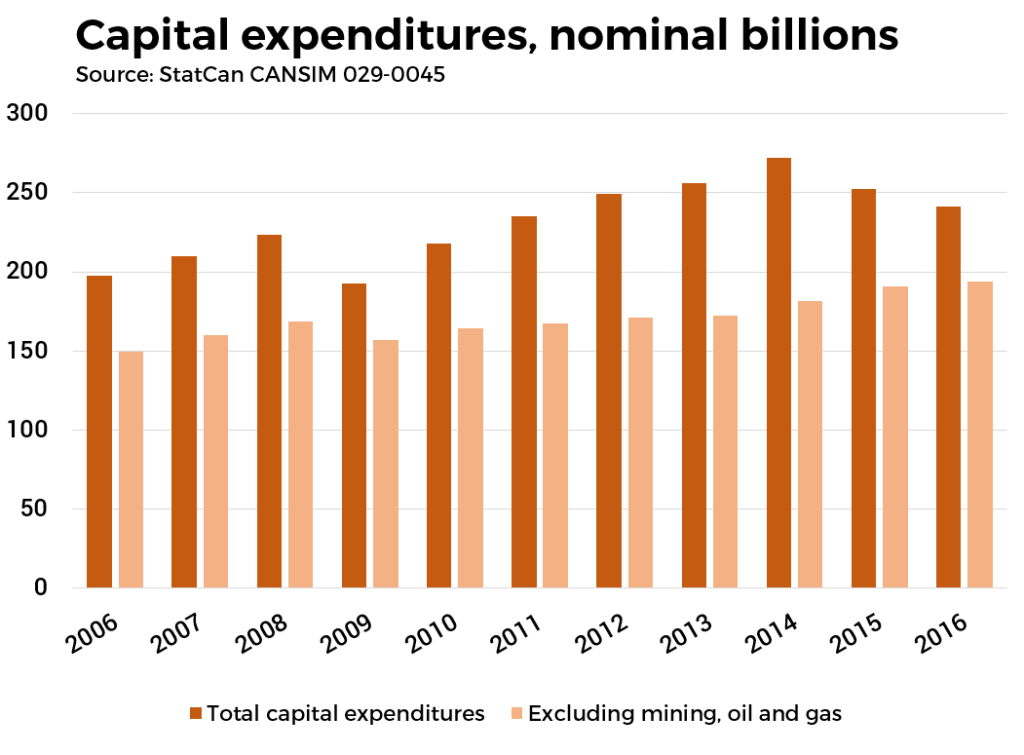

…and total investment, including that done by government, at home:

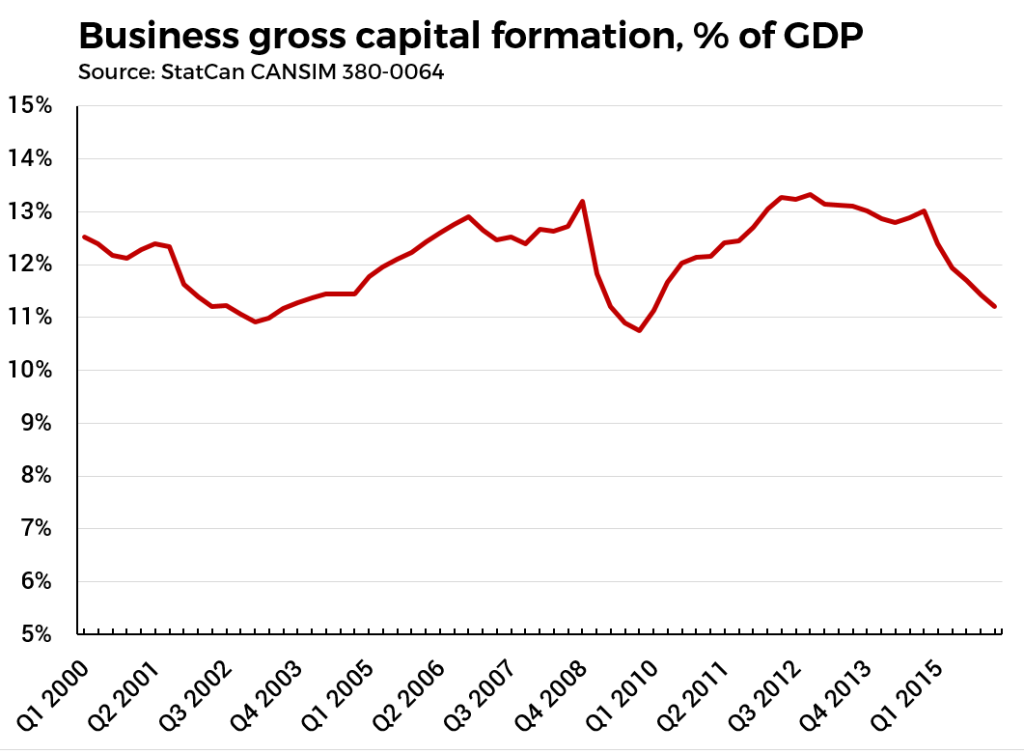

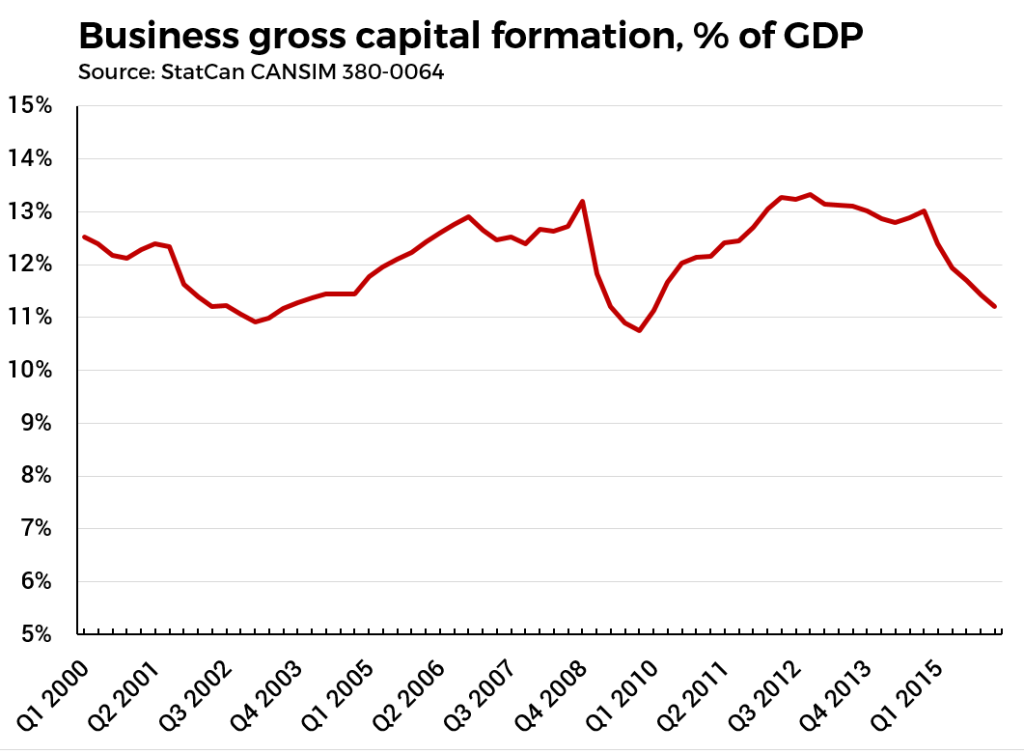

The chart above is in nominal dollars and includes all investment to make it easier to compare to the first chart. Here’s just business non-residential investment as a percentage of GDP. The uptick due to the resource boom in the early 2000s is clear; it’s instructive to imagine what things would have looked like if the resource sector had continued to expand at it’s long-term pre-boom average.

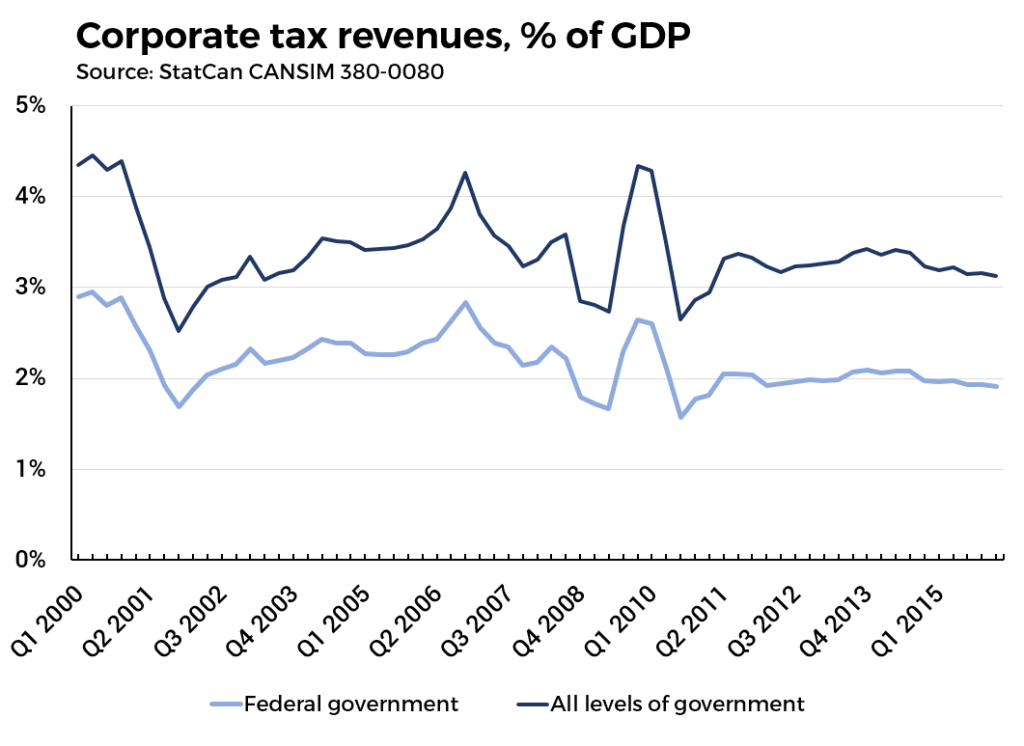

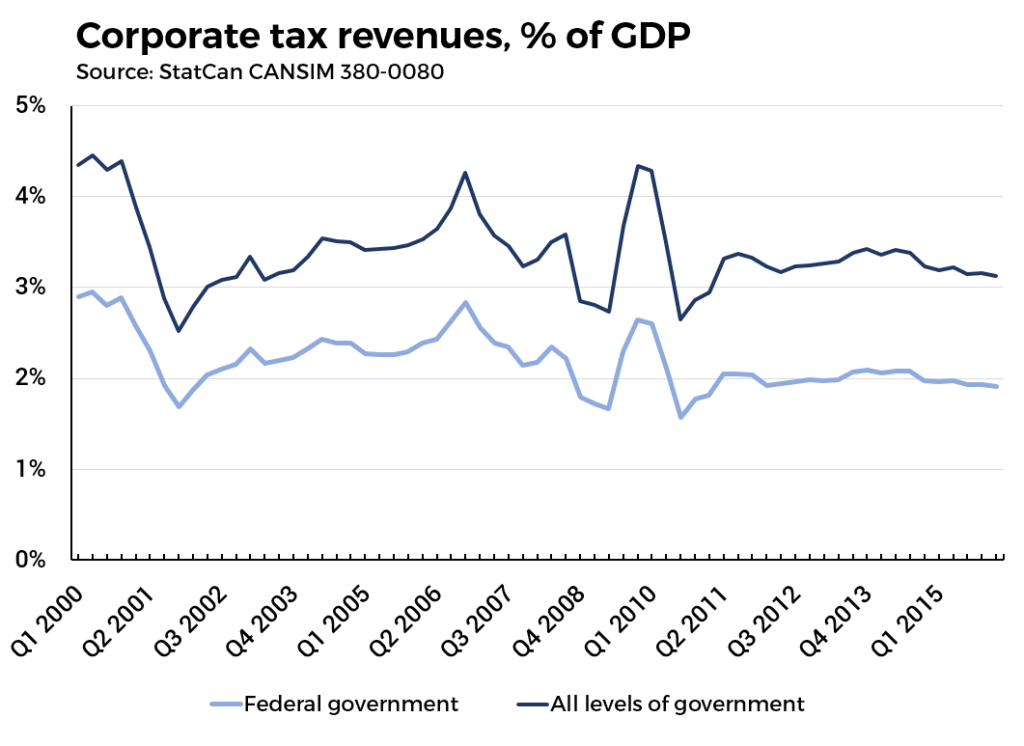

And finally, take a look at corporate tax receipts:

The contrast is striking. Corporations are piling cash into off-shore accounts while paying less in tax and barely keeping up with investment, especially outside the resource boom. Apologists would love to have a debate about the finer points of tax incidence, that is who ultimately pays a tax. They have a point; however, if it were so easy to always fully pass taxes on to consumers, why would corporations go to all the trouble of lobbying for tax breaks and making tax evasion so much easier? The answer is that it is ultimately a question of power. There is a question of how social wealth is divided up in the final accounting, but it comes down to who has the power to influence the division. Treaties with tax havens are just one instrument in the quiver.

A key and related next step would be to draw the links to the shareholder value revolution that has sought to remake corporations into ATMs for the wealthy. Rather than reinvest their profits into growth and productivity enhancements, corporations have, since roughly the early 1980s, been under increasing pressure to return a vast chunk of profits to shareholders via share buybacks and dividends. The corporate sector in the US is the poster child for the extract-what-you-can model but it turns out, for example, that a similar logic also played no small role in breaking the Eurozone financial system after the last crisis. What kind of tangible links are there between tax evasion and shareholder value for Canadian corporations?

In fact, when Mark Carney initially coined the “dead money” meme that has become an omnipresent shorthand on the left, he was not only exhorting corporations to invest. If they couldn’t, Carney said they should dish out more money to shareholders instead. Profits can pile up in bonds, shareholder pockets, cash or offshore accounts—the reality is that corporations are strategically choosing between competing allocations of assets, not stashing cash under a rug. Corporate money is never dead, and much of it is alive and well relaxing in Panama and the Bahamas. One thing is certain, it isn’t working for the rest of us.