How big is your deficit? This Ontario election, no one seems to care—and that’s a decisive positive to emerge from a campaign that’s too often been submerged in the politics of personality.

There is more and more light sneaking through the widening cracks in Canada’s austerity consensus. Hopefully, it will shine not only on the latest vote-buying scandal or bout of red-baiting but hit upon some of the big questions of economic policy. Here, the relevant question is not “how big is your deficit”, but “who will it benefit?” Or, put most expansively, “how are you going to transform the economy?”

In part, deficit panic has taken a back seat this election season because of an uncomfortable fact for those on the right usually most eager to stir it up. Mike Moffatt, economist at the centrist Canada 2020 think tank, has very roughly costed out the Conservatives’ platform (something the party has so far steadfastly refused to do) and found that their deficits would most likely be the largest among the three major parties. That’s the result of promising big tax cuts for companies large and small, car drivers, the wealthy, the upper middle class and other core Tory constituencies alongside insubstantial changes to spending. It is transformation biased towards the wealthy.

Doug Ford will protest that he will be able to generate “efficiencies”. These, however, will be either extremely painful cuts—think lay-offs for thousands of public sector workers like teachers, nurses, long-term care support staff or park rangers alongside fewer services—or an unkept promise. Decades of neoliberalism have created a lean public administration as much as the right won’t admit it in public. Anyone claiming to easily find $6 billion in efficiencies, or nearly 5% of Ontario’s budget, without shedding jobs or cutting services is simply lying.

The Ontario Liberals, surely emboldened by Justin Trudeau’s deficit-embracing, progressive neoliberalism, have also settled on steady, modest deficit spending. Deficits allow them to avoid raising taxes (the provincial corporate tax rate has kept falling on their watch) while continuing down the road of slow-motion austerity whose defining features are cost control and welfare state rationalization. Nothing to worry the financial markets and bond raters here. No real transformation either—the cuts of the Harris years are further baked in, only their rough edges softened.

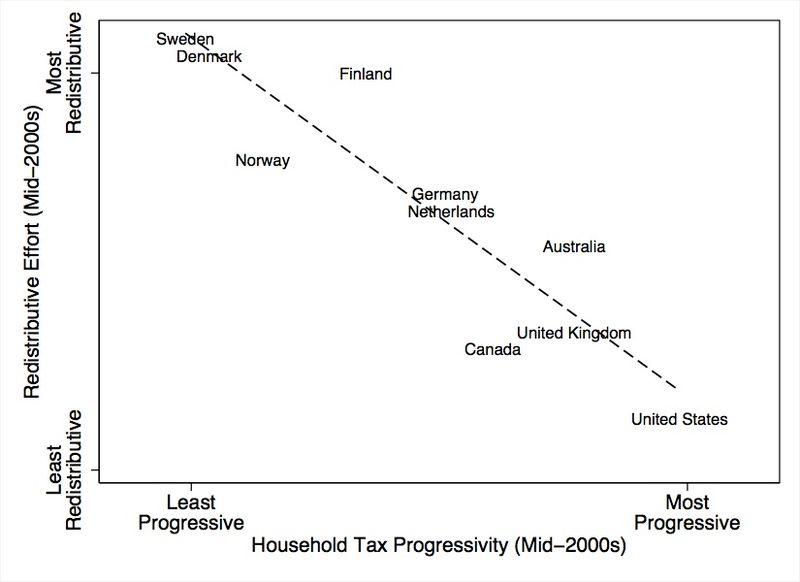

Chastised by their loss in 2014 and emboldened by deficits from everyone else, the NDP is also projecting modest deficits every year of its mandate if elected. These however are due to more substantial increases in both revenues and expenditures than the other two parties, with deficits generated by raising expenditures more than revenues. The important piece is not the deficit but what’s happening with the two components that produce it: expenditures and revenues. On the latter, the Ontario NDP have finally injected the smallest pinch of class politics into their policy, promising to raise taxes on both corporations and the wealthiest.