The scrappy mom-and-pop shop may be a nice image, but how well does it reflect the reality of employment? Small business may be neither as ubiquitous nor economically heroic as many people think. If this is the case, then perhaps the needs of small business should not figure as prominently in some economic policy debates. The minimum wage debate is a case in point.

Tag: Canada

The past few days have not been great for public services in Canada. Canada Post will be phasing out home delivery of mail. Expansion of the Canada Pension Plan was scuttled at the finance ministers’ meeting. In the grand scheme of things, however, these are not extreme cutbacks. It’s not as if Canada Post is to be dismantled completely or our public pension fund to run completely dry. This government has long brought us death by a thousand paper cuts and those from the past days are just a continuation of the strategy.

There is a particular common thread that runs through all such small cutbacks. Corey Robin’s recent article in Jacobin, “Socialism: Converting Hysterical Misery into Ordinary Unhappiness”, helped greatly in seeing and naming it. Let us call it insourcing.

This kind of insourcing refers to taking a collective public service and making it into an individual responsibility. Perhaps James Moore recently summed up the insourcing philosophy best, “Certainly we want to make sure that kids go to school full bellied, but is that always the government’s job to be there to serve people their breakfast?” Serve your own breakfast, get your own mail, don’t wait too long to die.

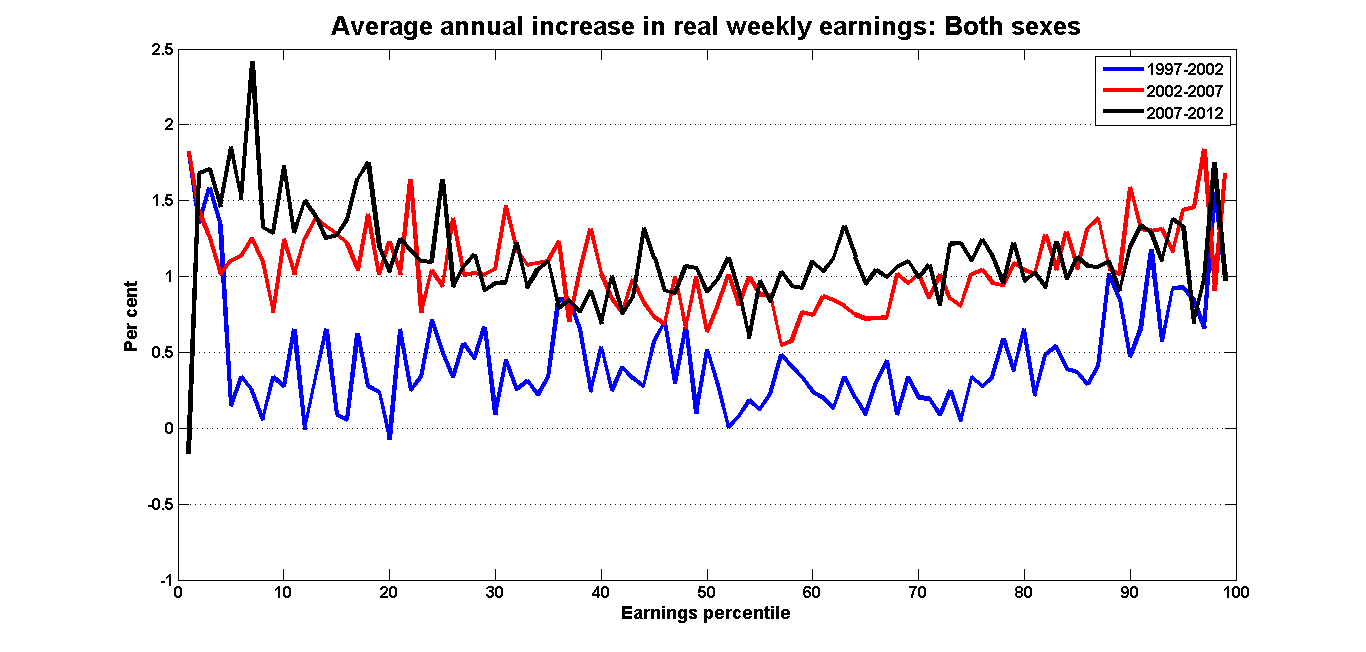

In a recent post titled, “What happened to the distribution of real earnings during the recession?”, Stephen Gordon presents a graphs that shows some significant growth in real (adjust for inflation) earnings in Canada between 2007 and 2012. In addition, plotting average annual growth rates in real earnings against the distribution of earnings, the graph has a U shape. That is, the growth rates of real earnings are higher for those at or near the bottom and those at or near the top of the earnings distribution, with a “hollowed-out” middle.

This graph, as well as several others presented by Gordon in this post and a previous article that show some sustained general growth in real earnings, goes against the received wisdom that real earnings have been stagnant, in Canada and across the world, for the past 30 or 40 years – especially so for low earners. What is behind the discrepancy between this new data and the long-standing trend? Gordon claims it is lower-than-expected inflation and, if not the active, then at least the passive policy of the Conservative government. I take issue with these claims.

This is the third and final post in what has become a three-part series on the puzzle of high profitability and low investment in the Canadian economy. In the first part, I looked at some data that shows the existence of the puzzle and explored a few of the factors that could be behind it. The follow-up post outlined broadly Keynesian and Marxian solutions aimed at raising investment: the former based on stimulating demand, the latter on eliminating overcapacity and increasing the relative profitability of productive capital. Here, I want to continue the thoughts that concluded the second part, namely that the Harper government’s preferred response to the puzzle has been neither demand stimulation nor industrial policy. Instead, it has been austerity – a strategy by no means accidental, but in fact designed to support the status quo of high profitability and low investment.

Austerity is not an isolated Canadian phenomenon nor is it a new one. The neoliberal era that began sometime in the 1970s has seen austerity in one form or another applied worldwide. Economic crises have especially provided governments with excuses to institute or continue austerity policies that would not have been difficult to institute otherwise. While Canada did not experience the latest economic crisis to the same extent as a number of other countries, it has seen a more moderate version of many of the same trends – such as slower growth and lower employment. The crisis was large enough to allow the Harper government to continue and deepen a tentative austerity regime. While Canada has not pursued austerity programs as spectacular as some, for example the UK or Spain, the Conservative government has, nevertheless, succeeded in substantially reducing the size of government, small cut by small cut. While Canadian austerity policies predate the crisis, the crisis has only helped to entrench them and further orient them towards propping up profitability.

Warning: A wonky, but thankfully short, post follows.

Yesterday, the Naked Capitalism blog reposted some recent research by OECD economist Eduardo Olaberria that looks at the effect of capital inflows on bubbles in assets, particularly housing. With so many other signs of a housing bubble forming in Canada, I decided to quickly see if the dangerous trends highlighted in this report are present in our economy today.

In my previous post, I outlined the disconnect between profitability and investment in Canada’s private sector. While businesses are doing well and profits have rebounded quickly after the global financial crisis of 2007, investment has continued its slow and steady 20-year decline. This decline is especially visible when investment is related directly to profits. Slightly more than 60% of gross profits are currently being re-invested, down by a third relative to just two decades ago. Such a gap between strong profitability and dismal investment does not correspond with standard accounts of how the economy functions. According to standard accounts, strong profitability should encourage investment, not depress it further. This theoretical relationship is not borne out in recent Canadian experience.

While the last post also examined a few factors that could have been at play in creating this odd state of affairs, here I want to move in the opposite direction and look at two competing pictures of how to revive low private-sector investment. The first picture comes from Keynes, the second from Marx. I am particularly indebted to Michael Roberts, who has written extensively on the crisis from a UK perspective and who used a similar framework in a recent article (on the adoption of the idea of a permanent slump by mainstream Keynesians).

The two pictures agree on a diagnosis of on-going stagnation – with low investment being just one feature. Indeed, the lack of sustained recovery across much of the developed world has led increasing numbers of mainstream economists to declare that the current slowdown is permanent. Paul Krugman, likely the most prominent Keynesian economist, recently wrote that we may have entered a “permanent slump.” Even the more hawkish Larry Summers has added his voice to the chorus, referring in a recent speech at the IMF to a period of “secular stagnation”. Many Marxist and other radical economists have, of course, been making the same point for years, citing a variety of structural changes and imbalances in the economy, particularly those that characterize the neoliberal period that began in the 1970s when the great post-war boom lost steam.

While their diagnosis may be similar, Keynesian and Marxian economists see the way out of the current long-term slump rather differently.

Most developed economies continue to experience fall-out from the financial crisis of 2007-8. The Eurozone has been most ravaged, but the US and UK have not fared much better. After the initial rebound from the most severe crisis, growth in many economies has been decelerating to the point that some are once again contracting in real terms. At the same time, unemployment remains high – hitting record levels among youth in Europe for example – real incomes are flat for the vast majority, inequality is on the rise and austerity programs targeted at social services are eating further into living standards.

Canada has partly bucked these trends. While the overall growth rate has not returned to pre-crisis levels, it has not done nearly as poorly as that in Europe or even the US. Other measures of economic well-being do not suggest the level of alarm felt in harder-hit economies. To give two examples, the Canadian unemployment rate has grown relatively modestly and the distribution of gains since the crisis has not been skewed towards the very top to the extreme that it has been in the US and elsewhere. The financial press is increasingly optimistic – just this past week cheering newly-released above-forecast quarterly growth figures – and the Conservative government remains steadfast in touting our supposed economic prudence and resilience.

Finally, but not least, Canadian corporations also have had it relatively good since the crisis. Other than a sharp dip around 2008, profits have remained high and growing.